| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Numerous recent studies examining some aspect of the achievement of English learners have been conducted (Abedi, 2008; Alvarez Greeson, 2008; Dean, 2006; Flynn, 2002; Karantinos, 2009; Olmstead, 2004; Pagan, 2005; Rodriguez, 2008; Weber, 2005). While the specific emphasis for each of these studies was different, a common finding was that certain factors matter more than others. For English learners, a key factor is language proficiency and the assessments that monitor and inform the language acquisition process (Abedi, 2008; Bielenberg&Wong Fillmore, 2004/2005; Cummins, 1981; Johnson, 2009; Kain&Singleton, 1996; Lee&Burkham, 2002; Marzano, 2004; Short&Echevarría, 2004/2005; Zwiers, 2004/2005). A second factor related to language proficiency and academic achievement is the ability to understand and use academic vocabulary for learning academic content (Aguila, 2010; Cummins, 2000; Dutro&Kinsella, 2010; Goldenberg&Coleman, 2010; Marzano&Pickering, 2005; Saunders&Goldenberg, 2010; Snow&Katz, 2010; Soto-Hinman&Hetzel, 2009). Language proficiency involves the ability to use and understand social and academic language in a variety of contexts. This level of vocabulary and language-use is constructed over time through explicit instruction that helps students to build the ability to understand and use the target language in all four language domains with attention to the purpose and the audience (Cummins, 1984; Snow&Katz, 2010).

Cummins (1981, 1984, 2000) described a theoretical framework for language proficiency as including three things. First, it needed to include a developmental viewpoint that accounted for levels of proficiency of both native speakers and language learners. The framework also needed to account for both social and academic discourse demands and had to include developmental connections between the primary and target languages.

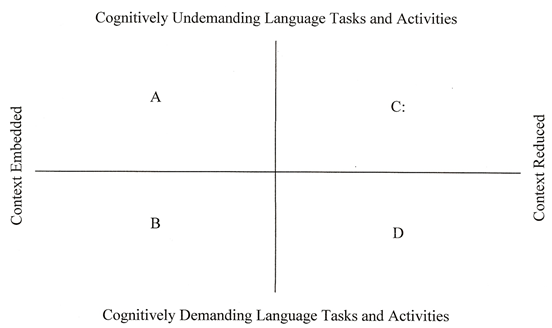

Based on the sociocultural context of schooling, the framework Cummins (2000) proposed included four quadrants along two continuums. The vertical continuum addressed the level of cognitive demand involved in the communication: the amount of information the learner needed to process in order to fully participate in the activity or communicative exchange. The horizontal continuum addressed the level of contextual support present in the communication that would support expression and reception of meaning (See Figure 1). Quadrant A represented context-embedded, cognitively undemanding communications as would be expected in social exchanges. Quadrant C also represented cognitively undemanding communications, but with less contextual support for the communication, much as would be expected for a phone call, for instance, on a familiar topic. Both quadrants B and D represented communicative tasks for which the person might not be as familiar with the vocabulary. As a result, these communications would require a significant level of cognitive energy to fully participate in the communication.

Figure 1. A representation of Cummins’ quadrants. Illustrates how each quadrant represents task demand. For example, tasks that fall in quadrant A are both context embedded and cognitively undemanding. Tasks in quadrant B are more language dependent but are scaffolded through the use of visuals to support comprehension. Adapted from Cummins, 1984.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Educational leadership and administration: teaching and program development, volume 23, 2011' conversation and receive update notifications?