| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

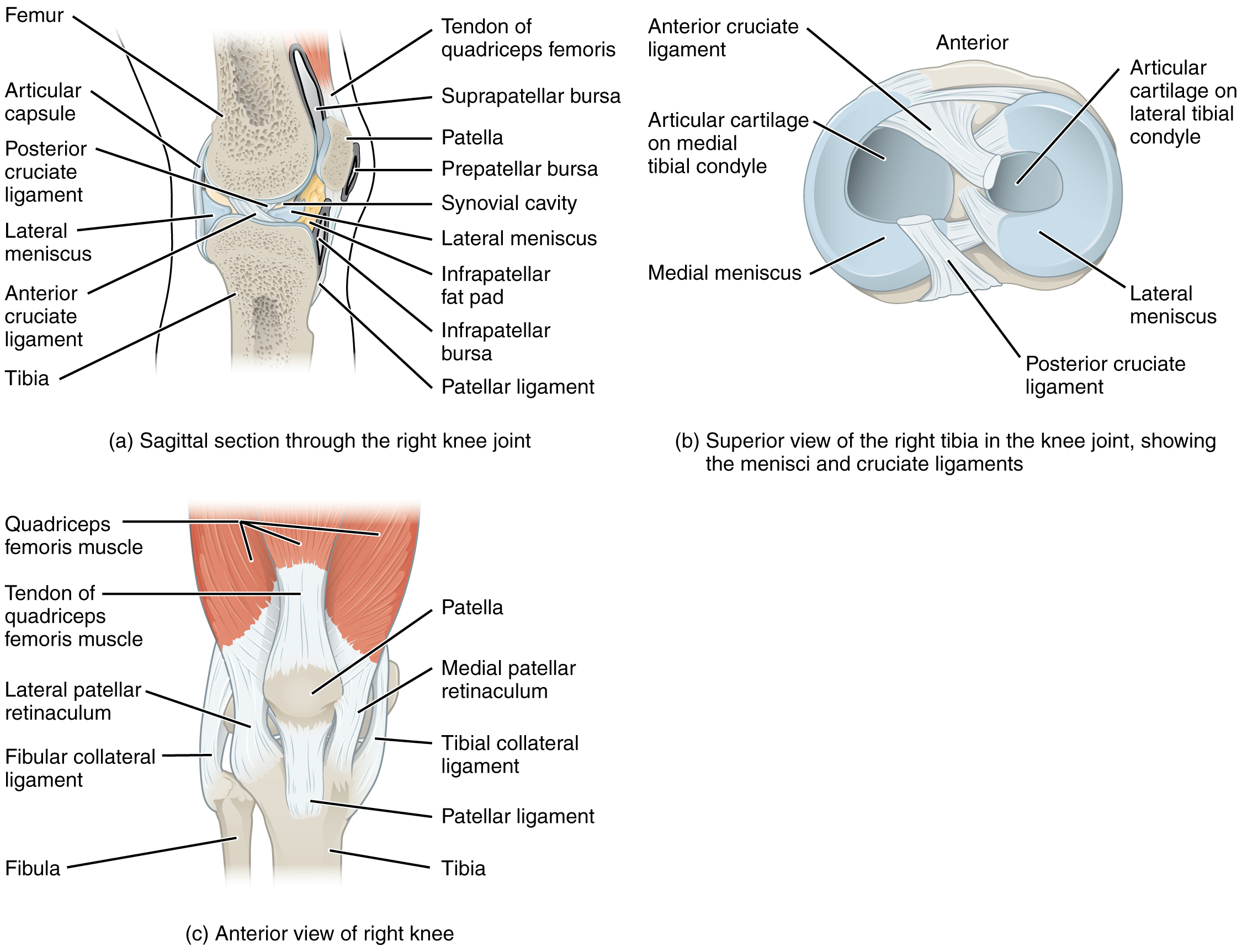

Located between the articulating surfaces of the femur and tibia are two articular discs, the medial meniscus and lateral meniscus (see [link] b ). Each is a C-shaped fibrocartilage structure that is thin along its inside margin and thick along the outer margin. They are attached to their tibial condyles, but do not attach to the femur. While both menisci are free to move during knee motions, the medial meniscus shows less movement because it is anchored at its outer margin to the articular capsule and tibial collateral ligament. The menisci provide padding between the bones and help to fill the gap between the round femoral condyles and flattened tibial condyles. Some areas of each meniscus lack an arterial blood supply and thus these areas heal poorly if damaged.

The knee joint has multiple ligaments that provide support, particularly in the extended position (see [link] c ). Outside of the articular capsule, located at the sides of the knee, are two extrinsic ligaments. The fibular collateral ligament (lateral collateral ligament) is on the lateral side and spans from the lateral epicondyle of the femur to the head of the fibula. The tibial collateral ligament (medial collateral ligament) of the medial knee runs from the medial epicondyle of the femur to the medial tibia. As it crosses the knee, the tibial collateral ligament is firmly attached on its deep side to the articular capsule and to the medial meniscus, an important factor when considering knee injuries. In the fully extended knee position, both collateral ligaments are taut (tight), thus serving to stabilize and support the extended knee and preventing side-to-side or rotational motions between the femur and tibia.

The articular capsule of the posterior knee is thickened by intrinsic ligaments that help to resist knee hyperextension. Inside the knee are two intracapsular ligaments, the anterior cruciate ligament and posterior cruciate ligament . These ligaments are anchored inferiorly to the tibia at the intercondylar eminence, the roughened area between the tibial condyles. The cruciate ligaments are named for whether they are attached anteriorly or posteriorly to this tibial region. Each ligament runs diagonally upward to attach to the inner aspect of a femoral condyle. The cruciate ligaments are named for the X-shape formed as they pass each other (cruciate means “cross”). The posterior cruciate ligament is the stronger ligament. It serves to support the knee when it is flexed and weight bearing, as when walking downhill. In this position, the posterior cruciate ligament prevents the femur from sliding anteriorly off the top of the tibia. The anterior cruciate ligament becomes tight when the knee is extended, and thus resists hyperextension.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Anatomy & Physiology: support and movement' conversation and receive update notifications?