| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

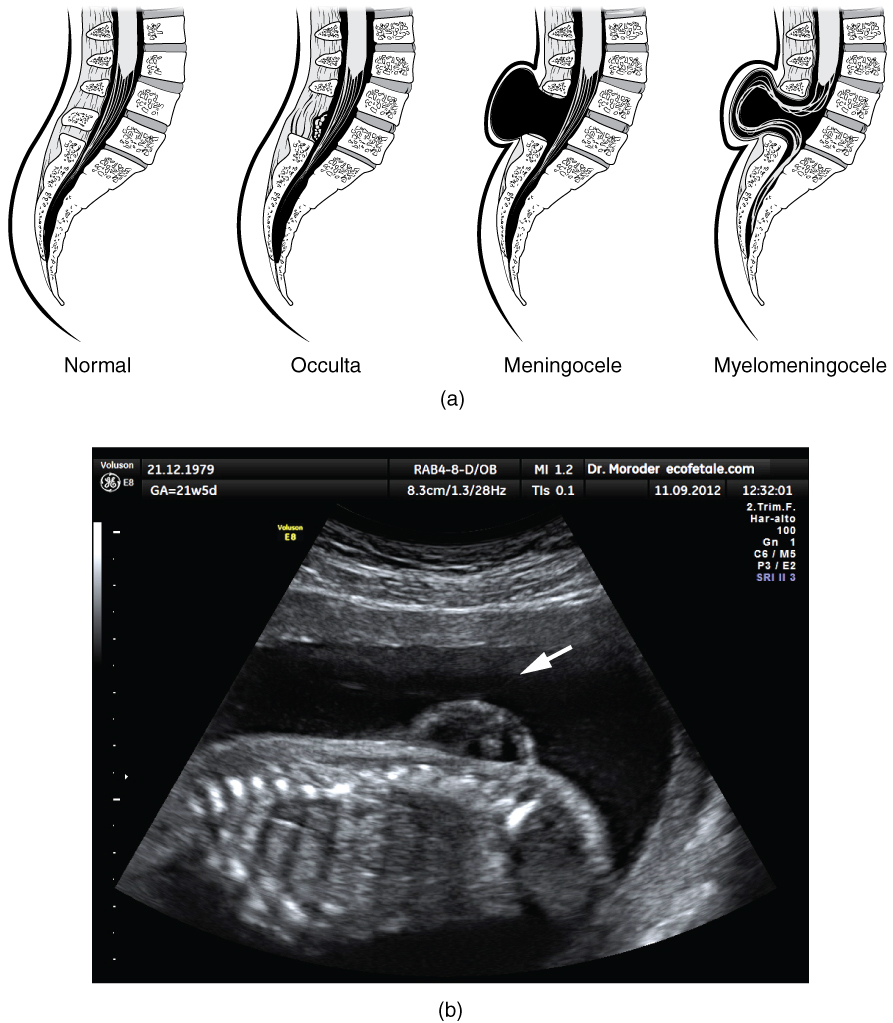

There are three classes of this disorder: occulta, meningocele, and myelomeningocele ( [link] ). The first type, spina bifida occulta, is the mildest because the vertebral bones do not fully surround the spinal cord, but the spinal cord itself is not affected. No functional differences may be noticed, which is what the word occulta means; it is hidden spina bifida. The other two types both involve the formation of a cyst—a fluid-filled sac of the connective tissues that cover the spinal cord called the meninges. “Meningocele” means that the meninges protrude through the spinal column but nerves may not be involved and few symptoms are present, though complications may arise later in life. “Myelomeningocele” means that the meninges protrude and spinal nerves are involved, and therefore severe neurological symptoms can be present.

Often surgery to close the opening or to remove the cyst is necessary. The earlier that surgery can be performed, the better the chances of controlling or limiting further damage or infection at the opening. For many children with meningocele, surgery will alleviate the pain, although they may experience some functional loss. Because the myelomeningocele form of spina bifida involves more extensive damage to the nervous tissue, neurological damage may persist, but symptoms can often be handled. Complications of the spinal cord may present later in life, but overall life expectancy is not reduced.

Watch this video to learn about the white matter in the cerebrum that develops during childhood and adolescence. This is a composite of MRI images taken of the brains of people from 5 years of age through 20 years of age, demonstrating how the cerebrum changes. As the color changes to blue, the ratio of gray matter to white matter changes. The caption for the video describes it as “less gray matter,” which is another way of saying “more white matter.” If the brain does not finish developing until approximately 20 years of age, can teenagers be held responsible for behaving badly?

The development of the nervous system starts early in embryonic development. The outer layer of the embryo, the ectoderm, gives rise to the skin and the nervous system. A specialized region of this layer, the neuroectoderm, becomes a groove that folds in and becomes the neural tube beneath the dorsal surface of the embryo. The anterior end of the neural tube develops into the brain, and the posterior region becomes the spinal cord. Tissues at the edges of the neural groove, when it closes off, are called the neural crest and migrate through the embryo to give rise to PNS structures as well as some non-nervous tissues.

The brain develops from this early tube structure and gives rise to specific regions of the adult brain. As the neural tube grows and differentiates, it enlarges into three vesicles that correspond to the forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain regions of the adult brain. Later in development, two of these three vesicles differentiate further, resulting in five vesicles. Those five vesicles can be aligned with the four major regions of the adult brain. The cerebrum is formed directly from the telencephalon. The diencephalon is the only region that keeps its embryonic name. The mesencephalon, metencephalon, and myelencephalon become the brain stem. The cerebellum also develops from the metencephalon and is a separate region of the adult brain.

The spinal cord develops out of the rest of the neural tube and retains the tube structure, with the nervous tissue thickening and the hollow center becoming a very small central canal through the cord. The rest of the hollow center of the neural tube corresponds to open spaces within the brain called the ventricles, where cerebrospinal fluid is found.

Watch this animation to examine the development of the brain, starting with the neural tube. As the anterior end of the neural tube develops, it enlarges into the primary vesicles that establish the forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain. Those structures continue to develop throughout the rest of embryonic development and into adolescence. They are the basis of the structure of the fully developed adult brain. How would you describe the difference in the relative sizes of the three regions of the brain when comparing the early (25th embryonic day) brain and the adult brain?

The three regions (forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain) appear to be approximately equal in size when they are first established, but the midbrain in the adult is much smaller than the others—suggesting that it does not increase in size nearly as much as the forebrain or hindbrain.

Watch this video to learn about the white matter in the cerebrum that develops during childhood and adolescence. This is a composite of MRI images taken of the brains of people from 5 years of age through 20 years of age, demonstrating how the cerebrum changes. As the color changes to blue, the ratio of gray matter to white matter changes. The caption for the video describes it as “less gray matter,” which is another way of saying “more white matter.” If the brain does not finish developing until approximately 20 years of age, can teenagers be held responsible for behaving badly?

This is really a matter of opinion, but there are ethical issues to consider when a teenager’s behavior results in legal trouble.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Anatomy & Physiology' conversation and receive update notifications?