| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

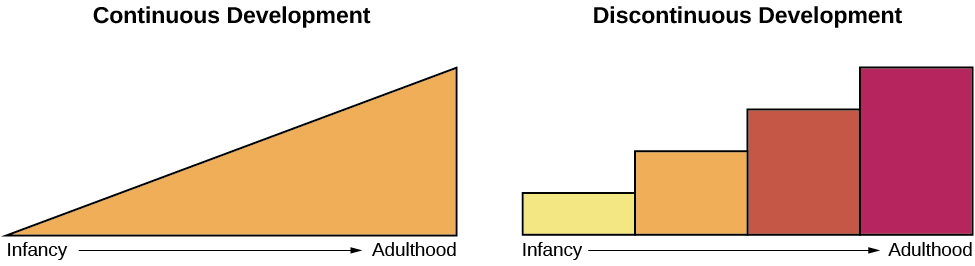

Continuous development views development as a cumulative process, gradually improving on existing skills ( [link] ). With this type of development, there is gradual change. Consider, for example, a child’s physical growth: adding inches to her height year by year. In contrast, theorists who view development as discontinuous believe that development takes place in unique stages: It occurs at specific times or ages. With this type of development, the change is more sudden, such as an infant’s ability to conceive object permanence.

Is development essentially the same, or universal, for all children (i.e., there is one course of development) or does development follow a different course for each child, depending on the child’s specific genetics and environment (i.e., there are many courses of development)? Do people across the world share more similarities or more differences in their development? How much do culture and genetics influence a child’s behavior?

Stage theories hold that the sequence of development is universal. For example, in cross-cultural studies of language development, children from around the world reach language milestones in a similar sequence (Gleitman&Newport, 1995). Infants in all cultures coo before they babble. They begin babbling at about the same age and utter their first word around 12 months old. Yet we live in diverse contexts that have a unique effect on each of us. For example, researchers once believed that motor development follows one course for all children regardless of culture. However, child care practices vary by culture, and different practices have been found to accelerate or inhibit achievement of developmental milestones such as sitting, crawling, and walking (Karasik, Adolph, Tamis-LeMonda,&Bornstein, 2010).

For instance, let’s look at the Aché society in Paraguay. They spend a significant amount of time foraging in forests. While foraging, Aché mothers carry their young children, rarely putting them down in order to protect them from getting hurt in the forest. Consequently, their children walk much later: They walk around 23–25 months old, in comparison to infants in Western cultures who begin to walk around 12 months old. However, as Aché children become older, they are allowed more freedom to move about, and by about age 9, their motor skills surpass those of U.S. children of the same age: Aché children are able to climb trees up to 25 feet tall and use machetes to chop their way through the forest (Kaplan&Dove, 1987). As you can see, our development is influenced by multiple contexts, so the timing of basic motor functions may vary across cultures. However, the functions themselves are present in all societies ( [link] ).

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Psychology' conversation and receive update notifications?