| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

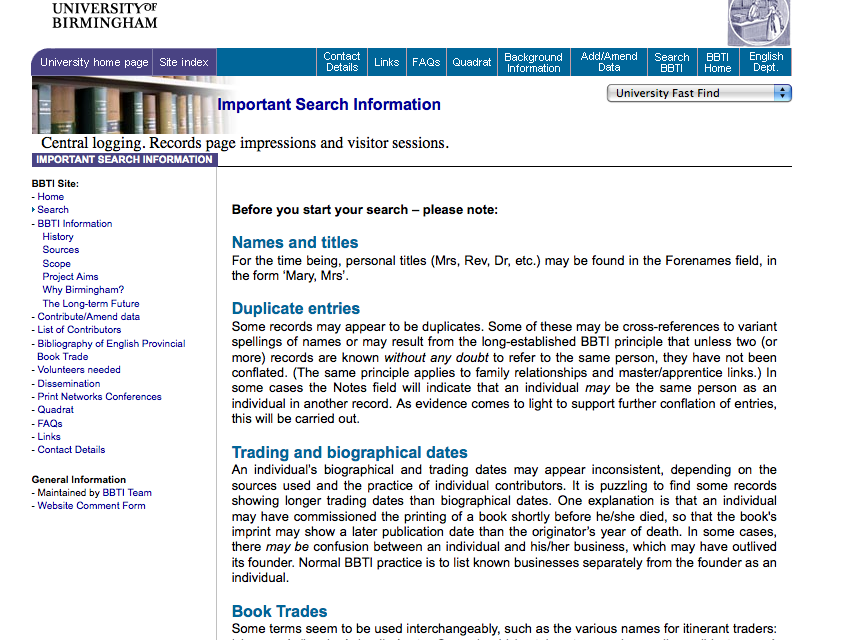

Much of Maxted’s work forms the basis of the British Book Trade Index, as one can see from their sources, though Maxted’s Topographical Guide is not (yet) listed among them. And yet, to what extent is the information even THERE, in that database? It is extractable, yes, but here is what one must go through to extract it:

By carefully following these guidelines, I could extract Maxted’s street-by-street list of booksellers, engravers, printers, etc. The addresses are given in the returns, beautifully, indicating the dates an entity occupied a particular address, but entry by entry. To get to that list of addresses by date, you have to click on each element in the returned list—each printer, bookseller, etc. So of course to understand the relationships among these printers and booksellers, one thing I would need to do is to generate lists of where they were during specific dates—lists of street addresses by year.

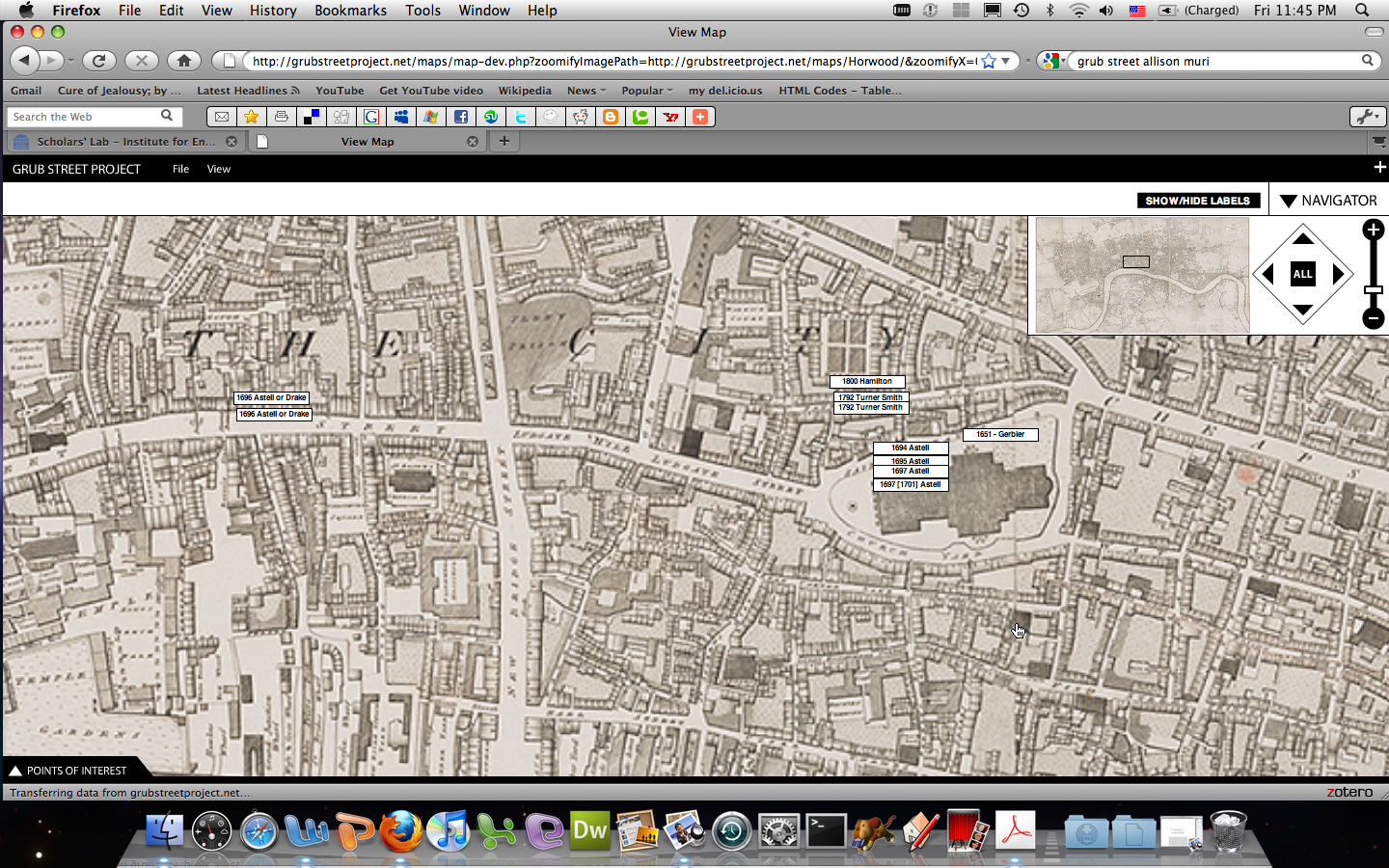

I submit, without further arguing, that Maxted’s Topographical Guide breaks both the book and the database medium: they cannot be used to effectively convey this information. The information of topographical relatedness, and all the possible research questions that go with it (“Location,” “Condition,” “Trend,” “Pattern,” given by Black and MacDonald, above), are lost in those particular material abstractions of print culture. We can only know the topography of printing by hooking that database up to maps—historical maps, which, as in Todd Presner’s Hyper-Berlin, offer different maps and mappings for different times. What we need, in other words, is Allison Muri’s Grub Street project.

Right now, Professor Muri has only begun to enter the information needed into the databases hooked up to her maps—currently, it is primarily the ESTC, I believe. What if we could know via map views specific to particular times precisely in which printing houses the feminist texts she maps here were printed?

What other kinds of texts were printed by the same printer and sold by the same bookseller? What collections of poetry came from those houses (and now I’m imagining linking my own Poetess Archive Database up to the Grub Street project), and whom did they include?

Professor Muri’s own idea is to go beyond even these socio-economic mappings to trace what she calls “patterns of literary motions”:

What might we discover if we map the “low-culture” of Grub Street communications alongside the “higher-order” communications of canonical authors . . . ? What are the relationships of shared, pirated, public, and freely-exchanged communications to furthering and encouraging practices of public creativity and knowledge? My preliminary task is to understand the passage of texts and books through the physical network (the streets) and the cultural network (the literature) of eighteenth-century London to see if I can gain insight into patterns of literary motions—the motions of texts, authors, books, and booksellers. Allison Muri, “The Technology and Future of the Book: What a Digital ‘Grub Street’ can tell us about Communications, Commerce, and Creativity,” in Producing the Eighteenth-Century Book: Writers and Publishers in England, 1650-1800 , ed. Laura Runge, Pat Rogers (Newark: Univ. of Delaware Press, 2009), pp. 235-251,

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Online humanities scholarship: the shape of things to come' conversation and receive update notifications?