| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

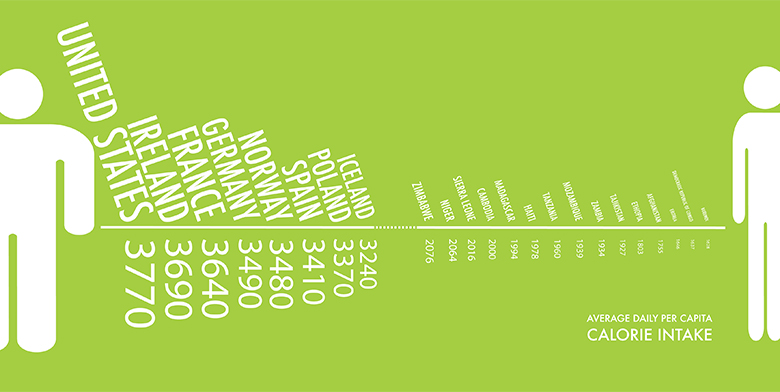

On average, humans need about 2,500 calories a day to survive, depending on height, weight, and gender. The economist Brad DeLong estimates that the average worker in the early 1600s earned wages that could afford him 2,500 food calories. This worker lived in Western Europe. Two hundred years later, that same worker could afford 3,000 food calories. However, between 1800 and 1875, just a time span of just 75 years, economic growth was so rapid that western European workers could purchase 5,000 food calories a day. By 2012, a low skilled worker in an affluent Western European/North American country could afford to purchase 2.4 million food calories per day.

What caused such a rapid rise in living standards between 1800 and 1875 and thereafter? Why is it that many countries, especially those in Western Europe, North America, and parts of East Asia, can feed their populations more than adequately, while others cannot? We will look at these and other questions as we examine long-run economic growth.

In this chapter, you will learn about:

Every country worries about economic growth. In the United States and other high-income countries, the question is whether economic growth continues to provide the same remarkable gains in our standard of living as it did during the twentieth century. Meanwhile, can middle-income countries like South Korea, Brazil, Egypt, or Poland catch up to the higher-income countries? Or must they remain in the second tier of per capita income? Of the world’s population of roughly 6.7 billion people, about 2.6 billion are scraping by on incomes that average less than $2 per day, not that different from the standard of living 2,000 years ago. Can the world’s poor be lifted from their fearful poverty? As the 1995 Nobel laureate in economics, Robert E. Lucas Jr., once noted: “The consequences for human welfare involved in questions like these are simply staggering: Once one starts to think about them, it is hard to think about anything else.”

Dramatic improvements in a nation’s standard of living are possible. After the Korean War in the late 1950s, the Republic of Korea, often called South Korea, was one of the poorest economies in the world. Most South Koreans worked in peasant agriculture. According to the British economist Angus Maddison, whose life’s work was the measurement of GDP and population in the world economy, GDP per capita in 1990 international dollars was $854 per year. From the 1960s to the early twenty-first century, a time period well within the lifetime and memory of many adults, the South Korean economy grew rapidly. Over these four decades, GDP per capita increased by more than 6% per year. According to the World Bank, GDP for South Korea now exceeds $30,000 in nominal terms, placing it firmly among high-income countries like Italy, New Zealand, and Israel. Measured by total GDP in 2012, South Korea is the thirteenth-largest economy in the world. For a nation of 49 million people, this transformation is extraordinary.

South Korea is a standout example, but it is not the only case of rapid and sustained economic growth. Other nations of East Asia, like Thailand and Indonesia, have seen very rapid growth as well. China has grown enormously since market-oriented economic reforms were enacted around 1980. GDP per capita in high-income economies like the United States also has grown dramatically albeit over a longer time frame. Since the Civil War, the U.S. economy has been transformed from a primarily rural and agricultural economy to an economy based on services, manufacturing, and technology.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Principles of economics' conversation and receive update notifications?