| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

In traditional physics, the discipline of complexity may yield insights in certain areas. Thermodynamics treats systems on the average, while statistical mechanics deals in some detail with complex systems of atoms and molecules in random thermal motion. Yet there is organization, adaptation, and evolution in those complex systems. Non-equilibrium phenomena, such as heat transfer and phase changes, are characteristically complex in detail, and new approaches to them may evolve from complexity as a discipline. Crystal growth is another example of self-organization spontaneously emerging in a complex system. Alloys are also inherently complex mixtures that show certain simple characteristics implying some self-organization. The organization of iron atoms into magnetic domains as they cool is another. Perhaps insights into these difficult areas will emerge from complexity. But at the minimum, the discipline of complexity is another example of human effort to understand and organize the universe around us, partly rooted in the discipline of physics.

A predecessor to complexity is the topic of chaos, which has been widely publicized and has become a discipline of its own. It is also based partly in physics and treats broad classes of phenomena from many disciplines. Chaos is a word used to describe systems whose outcomes are extremely sensitive to initial conditions. The orbit of the planet Pluto, for example, may be chaotic in that it can change tremendously due to small interactions with other planets. This makes its long-term behavior impossible to predict with precision, just as we cannot tell precisely where a decaying Earth satellite will land or how many pieces it will break into. But the discipline of chaos has found ways to deal with such systems and has been applied to apparently unrelated systems. For example, the heartbeat of people with certain types of potentially lethal arrhythmias seems to be chaotic, and this knowledge may allow more sophisticated monitoring and recognition of the need for intervention.

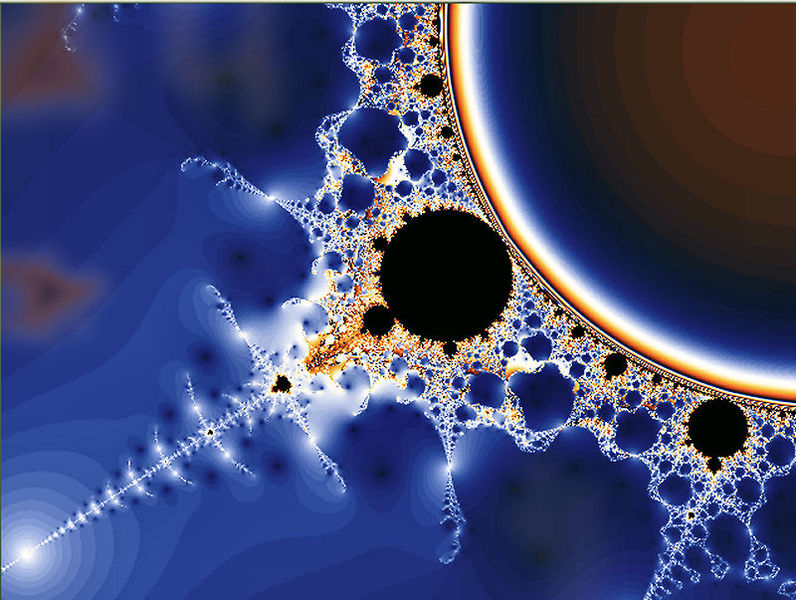

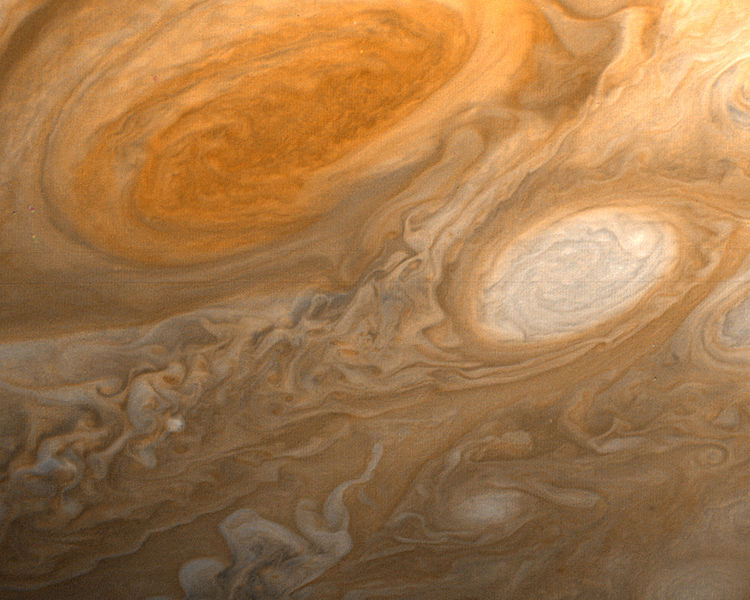

Chaos is related to complexity. Some chaotic systems are also inherently complex; for example, vortices in a fluid as opposed to a double pendulum. Both are chaotic and not predictable in the same sense as other systems. But there can be organization in chaos and it can also be quantified. Examples of chaotic systems are beautiful fractal patterns such as in [link] . Some chaotic systems exhibit self-organization, a type of stable chaos. The orbits of the planets in our solar system, for example, may be chaotic (we are not certain yet). But they are definitely organized and systematic, with a simple formula describing the orbital radii of the first eight planets and the asteroid belt. Large-scale vortices in Jupiter’s atmosphere are chaotic, but the Great Red Spot is a stable self-organization of rotational energy. (See [link] .) The Great Red Spot has been in existence for at least 400 years and is a complex self-adaptive system.

The emerging field of complexity, like the now almost traditional field of chaos, is partly rooted in physics. Both attempt to see similar systematics in a very broad range of phenomena and, hence, generate a better understanding of them. Time will tell what impact these fields have on more traditional areas of physics as well as on the other disciplines they relate to.

Must a complex system be adaptive to be of interest in the field of complexity? Give an example to support your answer.

State a necessary condition for a system to be chaotic.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'College physics' conversation and receive update notifications?