| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Find a flashlight that uses several batteries and find new and old batteries. Based on the discussions in this module, predict the brightness of the flashlight when different combinations of batteries are used. Do your predictions match what you observe? Now place new batteries in the flashlight and leave the flashlight switched on for several hours. Is the flashlight still quite bright? Do the same with the old batteries. Is the flashlight as bright when left on for the same length of time with old and new batteries? What does this say for the case when you are limited in the number of available new batteries?

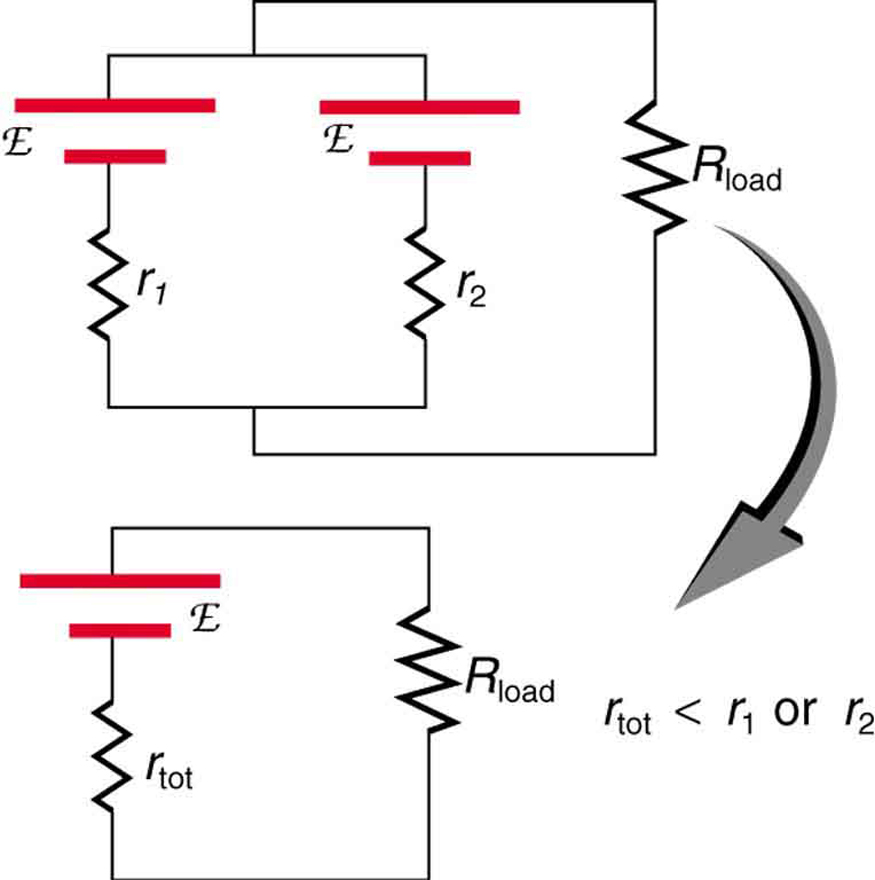

[link] shows two voltage sources with identical emfs in parallel and connected to a load resistance. In this simple case, the total emf is the same as the individual emfs. But the total internal resistance is reduced, since the internal resistances are in parallel. The parallel connection thus can produce a larger current.

Here, flows through the load, and is less than those of the individual batteries. For example, some diesel-powered cars use two 12-V batteries in parallel; they produce a total emf of 12 V but can deliver the larger current needed to start a diesel engine.

A number of animals both produce and detect electrical signals. Fish, sharks, platypuses, and echidnas (spiny anteaters) all detect electric fields generated by nerve activity in prey. Electric eels produce their own emf through biological cells (electric organs) called electroplaques, which are arranged in both series and parallel as a set of batteries.

Electroplaques are flat, disk-like cells; those of the electric eel have a voltage of 0.15 V across each one. These cells are usually located toward the head or tail of the animal, although in the case of the electric eel, they are found along the entire body. The electroplaques in the South American eel are arranged in 140 rows, with each row stretching horizontally along the body and containing 5,000 electroplaques. This can yield an emf of approximately 600 V, and a current of 1 A—deadly.

The mechanism for detection of external electric fields is similar to that for producing nerve signals in the cell through depolarization and repolarization—the movement of ions across the cell membrane. Within the fish, weak electric fields in the water produce a current in a gel-filled canal that runs from the skin to sensing cells, producing a nerve signal. The Australian platypus, one of the very few mammals that lay eggs, can detect fields of 30 , while sharks have been found to be able to sense a field in their snouts as small as 100 ( [link] ). Electric eels use their own electric fields produced by the electroplaques to stun their prey or enemies.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'College physics for ap® courses' conversation and receive update notifications?