| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Japanese forces won a series of early victories against Allied forces from December 1941 to May 1942. They seized Guam and Wake Island from the United States, and streamed through Malaysia and Thailand into the Philippines and through the Dutch East Indies. By February 1942, they were threatening Australia. The Allies turned the tide in May and June 1942, at the Battle of Coral Sea and the Battle of Midway. The Battle of Midway witnessed the first Japanese naval defeat since the nineteenth century. Shortly after the American victory, U.S. forces invaded Guadalcanal and New Guinea. Slowly, throughout 1943, the United States engaged in a campaign of “island hopping,” gradually moving across the Pacific to Japan. In 1944, the United States, seized Saipan and won the Battle of the Philippine Sea. Progressively, American forces drew closer to the strategically important targets of Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

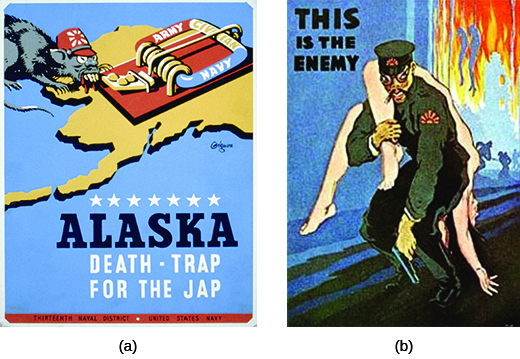

During the 1930s, Americans had caught glimpses of Japanese armies in action and grew increasingly sympathetic towards war-torn China. Stories of Japanese atrocities bordering on genocide and the shock of the attack on Pearl Harbor intensified racial animosity toward the Japanese. Wartime propaganda portrayed Japanese soldiers as uncivilized and barbaric, sometimes even inhuman ( [link] ), unlike America’s German foes. Admiral William Halsey spoke for many Americans when he urged them to “Kill Japs! Kill Japs! Kill more Japs!” Stories of the dispiriting defeats at Bataan and the Japanese capture of the Philippines at Corregidor in 1942 revealed the Japanese cruelty and mistreatment of Americans. The “Bataan Death March,” during which as many as 650 American and 10,000 Filipino prisoners of war died, intensified anti-Japanese feelings. Kamikaze attacks that took place towards the end of the war were regarded as proof of the irrationality of Japanese martial values and mindless loyalty to Emperor Hirohito.

Despite the Allies’ Europe First strategy, American forces took the resources that they could assemble and swung into action as quickly as they could to blunt the Japanese advance. Infuriated by stories of defeat at the hands of the allegedly racially inferior Japanese, many high-ranking American military leaders demanded that greater attention be paid to the Pacific campaign. Rather than simply wait for the invasion of France to begin, naval and army officers such as General Douglas MacArthur argued that American resources should be deployed in the Pacific to reclaim territory seized by Japan.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?