| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

The late nineteenth century was an energetic era of inventions and entrepreneurial spirit. Building upon the mid-century Industrial Revolution in Great Britain, as well as answering the increasing call from Americans for efficiency and comfort, the country found itself in the grip of invention fever, with more people working on their big ideas than ever before. In retrospect, harnessing the power of steam and then electricity in the nineteenth century vastly increased the power of man and machine, thus making other advances possible as the century progressed.

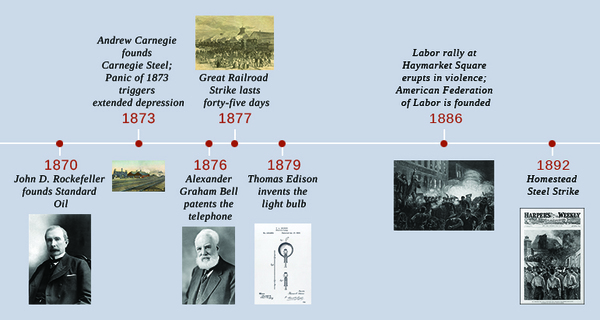

Facing an increasingly complex everyday life, Americans sought the means by which to cope with it. Inventions often provided the answers, even as the inventors themselves remained largely unaware of the life-changing nature of their ideas. To understand the scope of this zeal for creation, consider the U.S. Patent Office, which, in 1790—its first decade of existence—recorded only 276 inventions. By 1860, the office had issued a total of 60,000 patents. But between 1860 and 1890, that number exploded to nearly 450,000, with another 235,000 in the last decade of the century. While many of these patents came to naught, some inventions became lynchpins in the rise of big business and the country’s move towards an industrial-based economy, in which the desire for efficiency, comfort, and abundance could be more fully realized by most Americans.

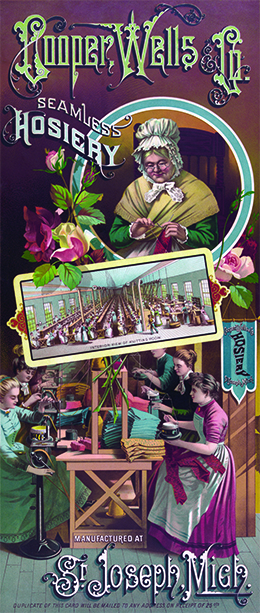

From corrugated rollers that could crack hard, homestead-grown wheat into flour to refrigerated train cars and garment-sewing machines ( [link] ), new inventions fueled industrial growth around the country. As late as 1880, fully one-half of all Americans still lived and worked on farms, whereas fewer than one in seven—mostly men, except for long-established textile factories in which female employees tended to dominate—were employed in factories. However, the development of commercial electricity by the close of the century, to complement the steam engines that already existed in many larger factories, permitted more industries to concentrate in cities, away from the previously essential water power. In turn, newly arrived immigrants sought employment in new urban factories. Immigration, urbanization, and industrialization coincided to transform the face of American society from primarily rural to significantly urban. From 1880 to 1920, the number of industrial workers in the nation quadrupled from 2.5 million to over 10 million, while over the same period urban populations doubled, to reach one-half of the country’s total population.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?