| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

When colonists came to the New World, they found a land that did not need “discovering” since it was already occupied. While the first wave of immigrants came from Western Europe, eventually the bulk of people entering North America were from Northern Europe, then Eastern Europe, then Latin America and Asia. And let us not forget the forced immigration of African slaves. Most of these groups underwent a period of disenfranchisement in which they were relegated to the bottom of the social hierarchy before they managed (for those who could) to achieve social mobility. Today, our society is multicultural, although the extent to which this multiculturality is embraced varies, and the many manifestations of multiculturalism carry significant political repercussions. The sections below will describe how several groups became part of U.S. society, discuss the history of intergroup relations for each faction, and assess each group’s status today.

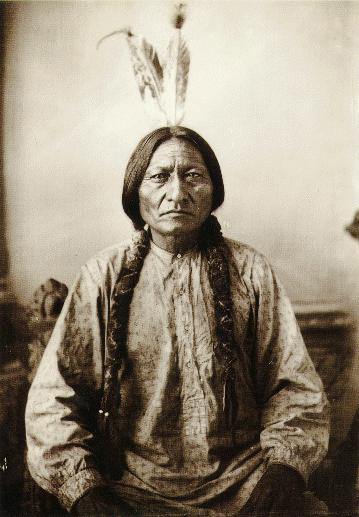

The only nonimmigrant ethnic group in the United States, Native Americans once numbered in the millions but by 2010 made up only 0.9 percent of U.S. populace; see above (U.S. Census 2010). Currently, about 2.9 million people identify themselves as Native American alone, while an additional 2.3 million identify them as Native American mixed with another ethnic group (Norris, Vines, and Hoeffel 2012).

The sports world abounds with team names like the Indians, the Warriors, the Braves, and even the Savages and Redskins. These names arise from historically prejudiced views of Native Americans as fierce, brave, and strong savages: attributes that would be beneficial to a sports team, but are not necessarily beneficial to people in the United States who should be seen as more than just fierce savages.

Since the civil rights movement of the 1960s, the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) has been campaigning against the use of such mascots, asserting that the “warrior savage myth . . . reinforces the racist view that Indians are uncivilized and uneducated and it has been used to justify policies of forced assimilation and destruction of Indian culture” (NCAI Resolution #TUL-05-087 2005). The campaign has met with only limited success. While some teams have changed their names, hundreds of professional, college, and K–12 school teams still have names derived from this stereotype. Another group, American Indian Cultural Support (AICS), is especially concerned with the use of such names at K–12 schools, influencing children when they should be gaining a fuller and more realistic understanding of Native Americans than such stereotypes supply.

What do you think about such names? Should they be allowed or banned? What argument would a symbolic interactionist make on this topic?

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Introduction to sociology 2e' conversation and receive update notifications?