| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

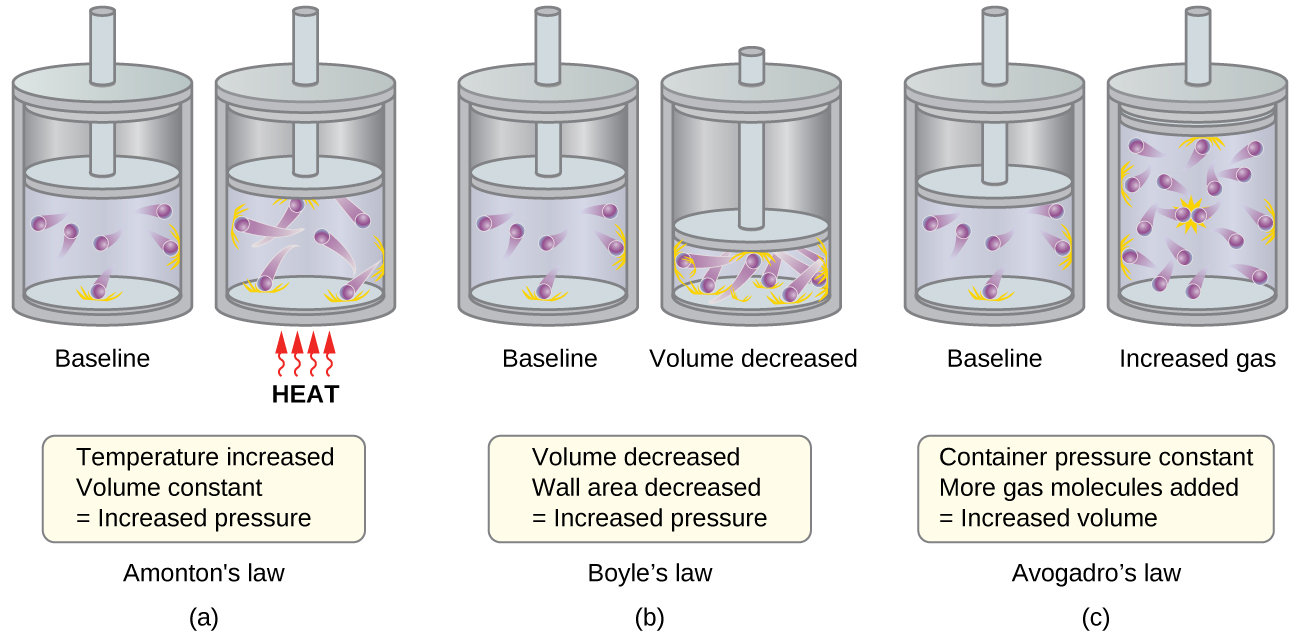

The previous discussion showed that the KMT qualitatively explains the behaviors described by the various gas laws. The postulates of this theory may be applied in a more quantitative fashion to derive these individual laws. To do this, we must first look at velocities and kinetic energies of gas molecules, and the temperature of a gas sample.

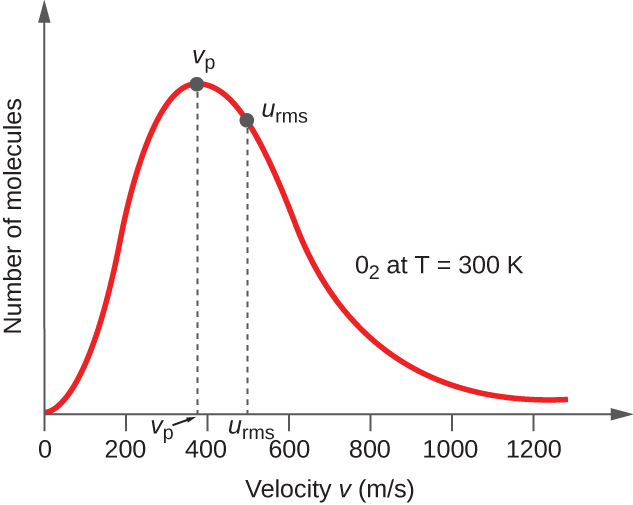

In a gas sample, individual molecules have widely varying speeds; however, because of the vast number of molecules and collisions involved, the molecular speed distribution and average speed are constant. This molecular speed distribution is known as a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution, and it depicts the relative numbers of molecules in a bulk sample of gas that possesses a given speed ( [link] ).

The kinetic energy (KE) of a particle of mass ( m ) and speed ( u ) is given by:

Expressing mass in kilograms and speed in meters per second will yield energy values in units of joules (J = kg m 2 s –2 ). To deal with a large number of gas molecules, we use averages for both speed and kinetic energy. In the KMT, the root mean square velocity of a particle, u rms , is defined as the square root of the average of the squares of the velocities with n = the number of particles:

The average kinetic energy, KE avg , is then equal to:

The KE avg of a collection of gas molecules is also directly proportional to the temperature of the gas and may be described by the equation:

where R is the gas constant and T is the kelvin temperature. When used in this equation, the appropriate form of the gas constant is 8.314 J/K (8.314 kg m 2 s –2 K –1 ). These two separate equations for KE avg may be combined and rearranged to yield a relation between molecular speed and temperature:

Determine the mass of a nitrogen molecule in kilograms:

Replace the variables and constants in the root-mean-square velocity equation, replacing Joules with the equivalent kg m 2 s –2 :

441 m/s

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Chemistry' conversation and receive update notifications?