| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Watch an animation of the move from free energy to transition state at this site.

Where does the activation energy required by chemical reactants come from? The source of the activation energy needed to push reactions forward is typically heat energy from the surroundings. Heat energy (the total bond energy of reactants or products in a chemical reaction) speeds up the motion of molecules, increasing the frequency and force with which they collide; it also moves atoms and bonds within the molecule slightly, helping them reach their transition state. For this reason, heating up a system will cause chemical reactants within that system to react more frequently. Increasing the pressure on a system has the same effect. Once reactants have absorbed enough heat energy from their surroundings to reach the transition state, the reaction will proceed.

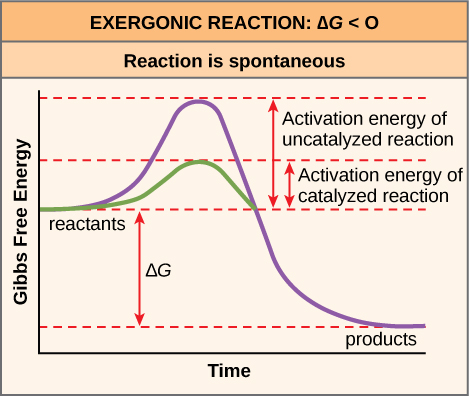

The activation energy of a particular reaction determines the rate at which it will proceed. The higher the activation energy, the slower the chemical reaction will be. The example of iron rusting illustrates an inherently slow reaction. This reaction occurs slowly over time because of its high E A . Additionally, the burning of many fuels, which is strongly exergonic, will take place at a negligible rate unless their activation energy is overcome by sufficient heat from a spark. Once they begin to burn, however, the chemical reactions release enough heat to continue the burning process, supplying the activation energy for surrounding fuel molecules. Like these reactions outside of cells, the activation energy for most cellular reactions is too high for heat energy to overcome at efficient rates. In other words, in order for important cellular reactions to occur at appreciable rates (number of reactions per unit time), their activation energies must be lowered ( [link] ); this is referred to as catalysis. This is a very good thing as far as living cells are concerned. Important macromolecules, such as proteins, DNA, and RNA, store considerable energy, and their breakdown is exergonic. If cellular temperatures alone provided enough heat energy for these exergonic reactions to overcome their activation barriers, the essential components of a cell would disintegrate.

If no activation energy were required to break down sucrose (table sugar), would you be able to store it in a sugar bowl?

Energy comes in many different forms. Objects in motion do physical work, and kinetic energy is the energy of objects in motion. Objects that are not in motion may have the potential to do work, and thus, have potential energy. Molecules also have potential energy because the breaking of molecular bonds has the potential to release energy. Living cells depend on the harvesting of potential energy from molecular bonds to perform work. Free energy is a measure of energy that is available to do work. The free energy of a system changes during energy transfers such as chemical reactions, and this change is referred to as ∆G.

The ∆G of a reaction can be negative or positive, meaning that the reaction releases energy or consumes energy, respectively. A reaction with a negative ∆G that gives off energy is called an exergonic reaction. One with a positive ∆G that requires energy input is called an endergonic reaction. Exergonic reactions are said to be spontaneous, because their products have less energy than their reactants. The products of endergonic reactions have a higher energy state than the reactants, and so these are nonspontaneous reactions. However, all reactions (including spontaneous -∆G reactions) require an initial input of energy in order to reach the transition state, at which they’ll proceed. This initial input of energy is called the activation energy.

[link] Look at each of the processes shown, and decide if it is endergonic or exergonic. In each case, does enthalpy increase or decrease, and does entropy increase or decrease?

[link] A compost pile decomposing is an exergonic process; enthalpy increases (energy is released) and entropy increases (large molecules are broken down into smaller ones). A baby developing from a fertilized egg is an endergonic process; enthalpy decreases (energy is absorbed) and entropy decreases. Sand art being destroyed is an exergonic process; there is no change in enthalpy, but entropy increases. A ball rolling downhill is an exergonic process; enthalpy decreases (energy is released), but there is no change in entropy.

[link] If no activation energy were required to break down sucrose (table sugar), would you be able to store it in a sugar bowl?

[link] No. We can store chemical energy because of the need to overcome the barrier to its breakdown.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Biology' conversation and receive update notifications?