| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Once it became clear that all matter was composed of particles that came to be called atoms, it also quickly became clear that the constituents of the atom included both positively charged particles and negatively charged particles. The next question was, what are the physical properties of those electrically charged particles?

The negatively charged particle was the first one to be discovered. In 1897, the English physicist J. J. Thomson was studying what was then known as cathode rays . Some years before, the English physicist William Crookes had shown that these “rays” were negatively charged, but his experiments were unable to tell any more than that. (The fact that they carried a negative electric charge was strong evidence that these were not rays at all, but particles.) Thomson prepared a pure beam of these particles and sent them through crossed electric and magnetic fields, and adjusted the various field strengths until the net deflection of the beam was zero. With this experiment, he was able to determine the charge-to-mass ratio of the particle. This ratio showed that the mass of the particle was much smaller than that of any other previously known particle—1837 times smaller, in fact. Eventually, this particle came to be called the electron .

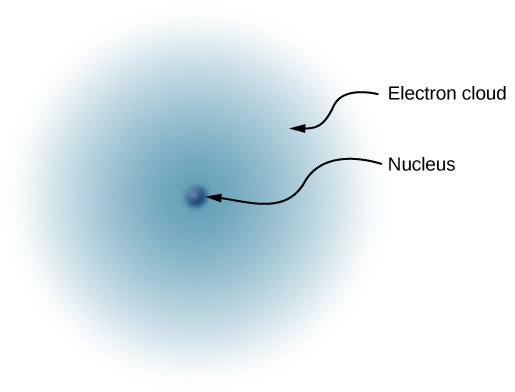

Since the atom as a whole is electrically neutral, the next question was to determine how the positive and negative charges are distributed within the atom. Thomson himself imagined that his electrons were embedded within a sort of positively charged paste, smeared out throughout the volume of the atom. However, in 1908, the New Zealand physicist Ernest Rutherford showed that the positive charges of the atom existed within a tiny core—called a nucleus —that took up only a very tiny fraction of the overall volume of the atom, but held over 99% of the mass. (See Linear Momentum and Collisions .) In addition, he showed that the negatively charged electrons perpetually orbited about this nucleus, forming a sort of electrically charged cloud that surrounds the nucleus ( [link] ). Rutherford concluded that the nucleus was constructed of small, massive particles that he named proton s .

Since it was known that different atoms have different masses, and that ordinarily atoms are electrically neutral, it was natural to suppose that different atoms have different numbers of protons in their nucleus, with an equal number of negatively charged electrons orbiting about the positively charged nucleus, thus making the atoms overall electrically neutral. However, it was soon discovered that although the lightest atom, hydrogen, did indeed have a single proton as its nucleus, the next heaviest atom—helium—has twice the number of protons (two), but four times the mass of hydrogen.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'University physics volume 2' conversation and receive update notifications?