| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

The English physicist William Gilbert (1544–1603) also studied this attractive force, using various substances. He worked with amber, and, in addition, he experimented with rock crystal and various precious and semi-precious gemstones. He also experimented with several metals. He found that the metals never exhibited this force, whereas the minerals did. Moreover, although an electrified amber rod would attract a piece of fur, it would repel another electrified amber rod; similarly, two electrified pieces of fur would repel each other.

This suggested there were two types of an electric property; this property eventually came to be called electric charge . The difference between the two types of electric charge is in the directions of the electric forces that each type of charge causes: These forces are repulsive when the same type of charge exists on two interacting objects and attractive when the charges are of opposite types. The SI unit of electric charge is the coulomb (C), after the French physicist Charles Augustine de Coulomb (1736–1806).

The most peculiar aspect of this new force is that it does not require physical contact between the two objects in order to cause an acceleration. This is an example of a so-called “long-range” force. (Or, as Albert Einstein later phrased it, “action at a distance.”) With the exception of gravity, all other forces we have discussed so far act only when the two interacting objects actually touch.

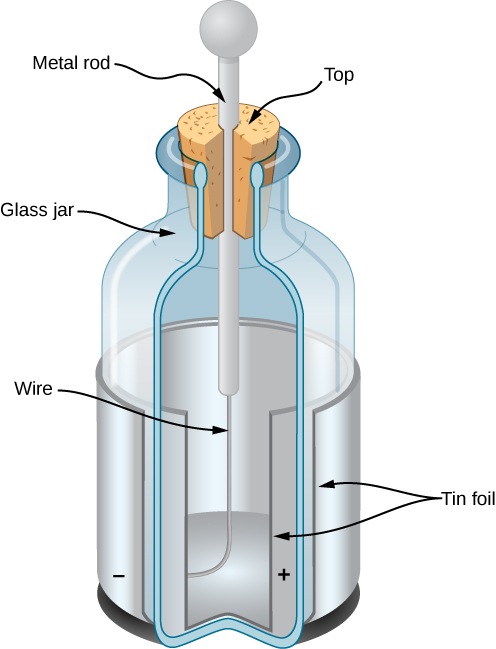

The American physicist and statesman Benjamin Franklin found that he could concentrate charge in a “ Leyden jar ,” which was essentially a glass jar with two sheets of metal foil, one inside and one outside, with the glass between them ( [link] ). This created a large electric force between the two foil sheets.

Franklin pointed out that the observed behavior could be explained by supposing that one of the two types of charge remained motionless, while the other type of charge flowed from one piece of foil to the other. He further suggested that an excess of what he called this “electrical fluid” be called “positive electricity” and the deficiency of it be called “negative electricity.” His suggestion, with some minor modifications, is the model we use today. (With the experiments that he was able to do, this was a pure guess; he had no way of actually determining the sign of the moving charge. Unfortunately, he guessed wrong; we now know that the charges that flow are the ones Franklin labeled negative, and the positive charges remain largely motionless. Fortunately, as we’ll see, it makes no practical or theoretical difference which choice we make, as long as we stay consistent with our choice.)

Let’s list the specific observations that we have of this electric force :

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'University physics volume 2' conversation and receive update notifications?