| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

[link] shows the density of water in various phases and temperature. The density of water increases with decreasing temperature, reaching a maximum at and then decreases as the temperature falls below . This behavior of the density of water explains why ice forms at the top of a body of water.

| Substance | |

|---|---|

| Ice | |

| Water | |

| Water | |

| Water | |

| Water | |

| Steam | |

| Sea water |

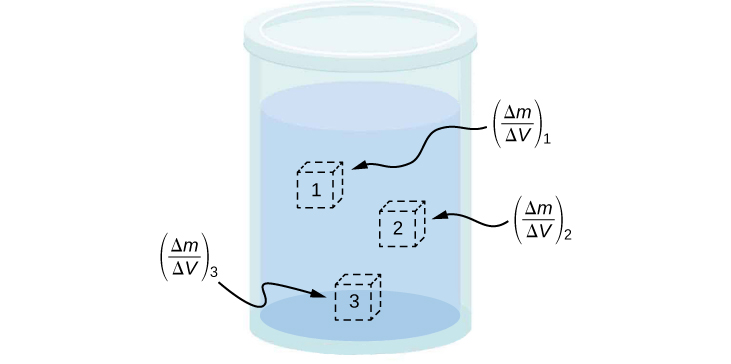

The density of a substance is not necessarily constant throughout the volume of a substance. If the density is constant throughout a substance, the substance is said to be a homogeneous substance . A solid iron bar is an example of a homogeneous substance. The density is constant throughout, and the density of any sample of the substance is the same as its average density. If the density of a substance were not constant, the substance is said to be a heterogeneous substance . A chunk of Swiss cheese is an example of a heterogeneous material containing both the solid cheese and gas-filled voids. The density at a specific location within a heterogeneous material is called local density , and is given as a function of location, ( [link] ).

Local density can be obtained by a limiting process, based on the average density in a small volume around the point in question, taking the limit where the size of the volume approaches zero,

where is the density, m is the mass, and V is the volume.

Since gases are free to expand and contract, the densities of the gases vary considerably with temperature, whereas the densities of liquids vary little with temperature. Therefore, the densities of liquids are often treated as constant, with the density equal to the average density.

Density is a dimensional property; therefore, when comparing the densities of two substances, the units must be taken into consideration. For this reason, a more convenient, dimensionless quantity called the specific gravity is often used to compare densities. Specific gravity is defined as the ratio of the density of the material to the density of water at and one atmosphere of pressure, which is :

The comparison uses water because the density of water is , which was originally used to define the kilogram. Specific gravity, being dimensionless, provides a ready comparison among materials without having to worry about the unit of density. For instance, the density of aluminum is 2.7 in (2700 in ), but its specific gravity is 2.7, regardless of the unit of density. Specific gravity is a particularly useful quantity with regard to buoyancy, which we will discuss later in this chapter.

You have no doubt heard the word ‘pressure’ used in relation to blood (high or low blood pressure) and in relation to weather (high- and low-pressure weather systems). These are only two of many examples of pressure in fluids. (Recall that we introduced the idea of pressure in Static Equilibrium and Elasticity , in the context of bulk stress and strain.)

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'University physics volume 1' conversation and receive update notifications?