| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

The information presented in this section supports the following AP® learning objectives and science practices:

Falling objects form an interesting class of motion problems. For example, we can estimate the depth of a vertical mine shaft by dropping a rock into it and listening for the rock to hit the bottom. By applying the kinematics developed so far to falling objects, we can examine some interesting situations and learn much about gravity in the process.

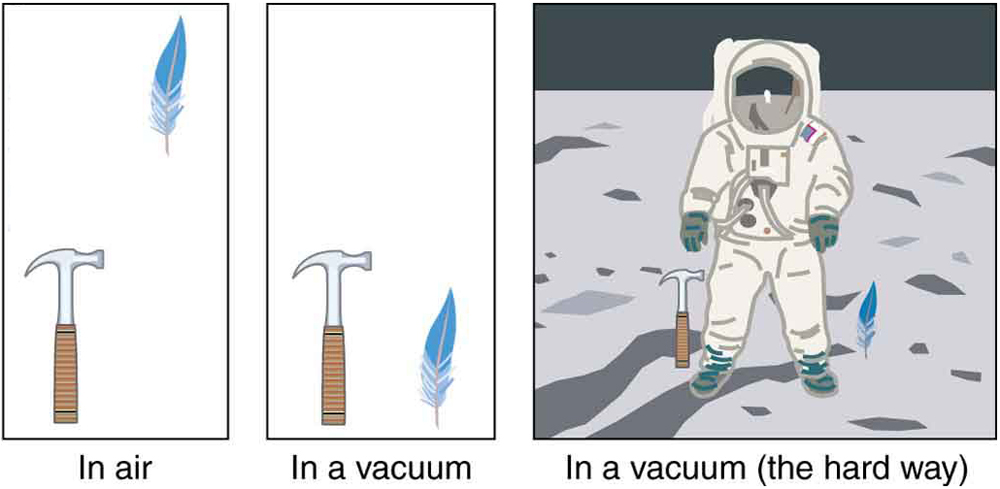

The most remarkable and unexpected fact about falling objects is that, if air resistance and friction are negligible, then in a given location all objects fall toward the center of Earth with the same constant acceleration , independent of their mass . This experimentally determined fact is unexpected, because we are so accustomed to the effects of air resistance and friction that we expect light objects to fall slower than heavy ones.

In the real world, air resistance can cause a lighter object to fall slower than a heavier object of the same size. A tennis ball will reach the ground after a hard baseball dropped at the same time. (It might be difficult to observe the difference if the height is not large.) Air resistance opposes the motion of an object through the air, while friction between objects—such as between clothes and a laundry chute or between a stone and a pool into which it is dropped—also opposes motion between them. For the ideal situations of these first few chapters, an object falling without air resistance or friction is defined to be in free-fall .

The force of gravity causes objects to fall toward the center of Earth. The acceleration of free-falling objects is therefore called the acceleration due to gravity . The acceleration due to gravity is constant , which means we can apply the kinematics equations to any falling object where air resistance and friction are negligible. This opens a broad class of interesting situations to us. The acceleration due to gravity is so important that its magnitude is given its own symbol, . It is constant at any given location on Earth and has the average value

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'College physics for ap® courses' conversation and receive update notifications?