| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

One consequence or use of the wave nature of matter is found in the electron microscope. As we have discussed, there is a limit to the detail observed with any probe having a wavelength. Resolution, or observable detail, is limited to about one wavelength. Since a potential of only 54 V can produce electrons with sub-nanometer wavelengths, it is easy to get electrons with much smaller wavelengths than those of visible light (hundreds of nanometers). Electron microscopes can, thus, be constructed to detect much smaller details than optical microscopes. (See [link] .)

There are basically two types of electron microscopes. The transmission electron microscope (TEM) accelerates electrons that are emitted from a hot filament (the cathode). The beam is broadened and then passes through the sample. A magnetic lens focuses the beam image onto a fluorescent screen, a photographic plate, or (most probably) a CCD (light sensitive camera), from which it is transferred to a computer. The TEM is similar to the optical microscope, but it requires a thin sample examined in a vacuum. However it can resolve details as small as 0.1 nm ( ), providing magnifications of 100 million times the size of the original object. The TEM has allowed us to see individual atoms and structure of cell nuclei.

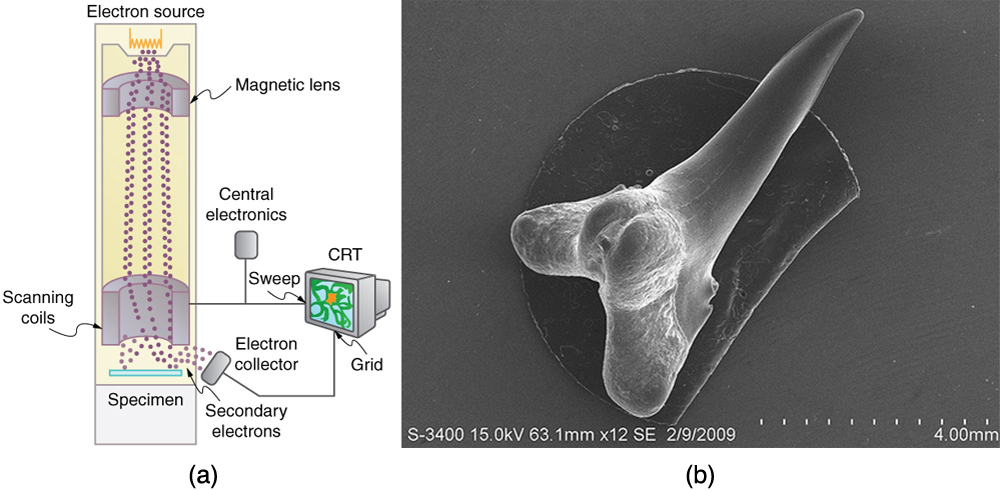

The scanning electron microscope (SEM) provides images by using secondary electrons produced by the primary beam interacting with the surface of the sample (see [link] ). The SEM also uses magnetic lenses to focus the beam onto the sample. However, it moves the beam around electrically to “scan” the sample in the x and y directions. A CCD detector is used to process the data for each electron position, producing images like the one at the beginning of this chapter. The SEM has the advantage of not requiring a thin sample and of providing a 3-D view. However, its resolution is about ten times less than a TEM.

Electrons were the first particles with mass to be directly confirmed to have the wavelength proposed by de Broglie. Subsequently, protons, helium nuclei, neutrons, and many others have been observed to exhibit interference when they interact with objects having sizes similar to their de Broglie wavelength. The de Broglie wavelength for massless particles was well established in the 1920s for photons, and it has since been observed that all massless particles have a de Broglie wavelength The wave nature of all particles is a universal characteristic of nature. We shall see in following sections that implications of the de Broglie wavelength include the quantization of energy in atoms and molecules, and an alteration of our basic view of nature on the microscopic scale. The next section, for example, shows that there are limits to the precision with which we may make predictions, regardless of how hard we try. There are even limits to the precision with which we may measure an object’s location or energy.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'College physics for ap® courses' conversation and receive update notifications?