| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

*Data extracted from Whitfield 1998, Whitefield 2003 and Dowton 2001

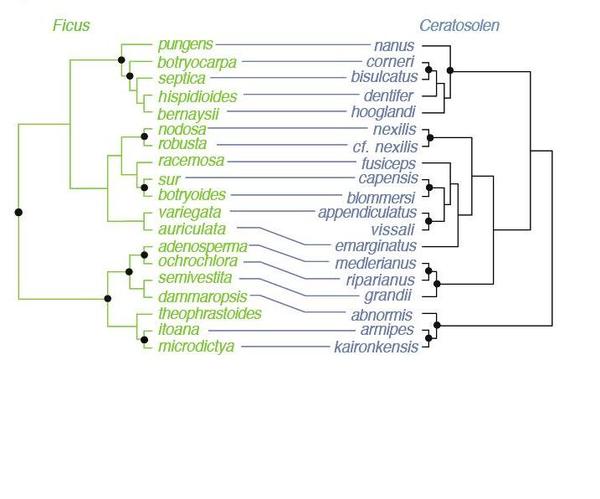

Parasite lineages tend to parallel those of their hosts (Brooks and McLennan, 1993). A number of studies have shown patterns of coevolution between parasitoid wasps and their hosts. Fig-pollinating wasps, which originated from a parasitoid ancestor, appear to have evolved in response to their host plants (Machado et al., 2001).

The relationship between parasitoid and host is attributed to mortality risk (Strand, 2000). A trade-off exists between size and development time – an organism must choose between growing larger at the cost of greater mortality risk due to increased development time and developing rapidly to reduce mortality risk at the cost of reduced size (Abrams, 1996). Thus, conditions that increase development time increase risk of mortality for both the host and parasitoid. Because of this trade-off, parasitoids that face high mortality risk favor shorter development times and are smaller. Conversely, species that face low mortality risks favor size at the cost of increased development time. Parasitoids that attack exposed species appear to experience higher levels of intraguild competition than parasitoids that attack concealed hosts (Blackburn, 1991). In response to this increase in mortality risk, parasitoids that attack exposed hosts have shorter development times.

Although this paper focuses on parasitism of insect hosts, wasps also parasitize plants. Like many other mutualisms, the fig-pollinator association has been exploited by wasp parasites (Yu, 2001). One fig species can host up to 30 different species of nonpollinating fig wasps. Niche space within the syconium is separated by different subsets of flowers, timing of oviposition, and by larval diets. Nonpollinating fig wasps can be split into different functional groups (Cook and Rasplus, 2003):

It has been hypothesized that figs do not exclude nonpollinating fig wasps because defenses against these parasitoid wasps might also exclude necessary pollinators (Cook and Rasplus, 2003). Some parasitoid wasps use the same cues as pollinators to oviposit at the same time, and defenses against these wasps might come at the cost of attracting pollinators to disperse seeds.

Another factor related to development time is fecundity. Parasitoids must compensate for the increase in mortality risk that accompanies host exposure. Therefore, parasitoid fecundity is expected to rise as opportunities of finding hosts increases and the probability of offspring surviving to adulthood declines (Price, 1980). Early host stages such as eggs and young larvae are more abundant and exposed than later host stages, so parasitoids that attack young hosts are expected to have larger fecundities than those who attack older hosts. Conversely, parasitoids that attack concealed hosts are predicted to have lower fecundities (Price, 1980). As predicted, wasps that parasitize young larvae are associated with higher fecundities and are typically endoparasitic koinobionts, while wasps that parasitize pupae are associated with lower fecundities and are typically idiobionts (Mayhew and Blackburn, 1999).

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Mockingbird tales: readings in animal behavior' conversation and receive update notifications?