| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

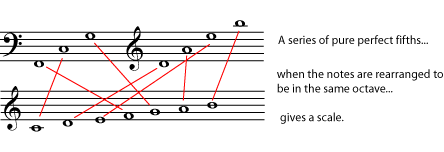

The main weakness of the Pythagorean system is that a series of pure perfect fifths will never take you to a note that is a pure octave above the note you started on. To see why this is a problem, imagine beginning on a C. A series of perfect fifths would give: C, G, D, A, E, B, F sharp, C sharp, G sharp, D sharp, A sharp, E sharp, and B sharp. In equal temperament (which doesn't use pure fifths), that B sharp would be exactly the same pitch as the C seven octaves above where you started (so that the series can, in essence, be turned into a closed loop, the Circle of Fifths ). Unfortunately, the B sharp that you arrive at after a series of pure fifths is a little higher than that C.

So in order to keep pure octaves, instruments that use Pythagorean tuning have to use eleven pure fifths and one smaller fifth. The smaller fifth has traditionally been called a wolf fifth because of its unpleasant sound. Keys that avoid the wolf fifth sound just fine on instruments that are tuned this way, but keys in which the wolf fifth is often heard become a problem. To avoid some of the harshness of the wolf intervals, some harpsichords and other keyboard instruments were built with split keys for D sharp/E flat and for G sharp/A flat. The front half of the key would play one note, and the back half the other (differently tuned) note.

Pythagorean tuning was widely used in medieval and Renaissance times. Major seconds and thirds are larger in Pythagorean intonation than in equal temperament, and minor seconds and thirds are smaller. Some people feel that using such intervals in medieval music is not only more authentic, but sounds better too, since the music was composed for this tuning system.

More modern Western music, on the other hand, does not sound pleasant using Pythagorean intonation. Although the fifths sound great, the thirds are simply too far away from the pure major and minor thirds of the harmonic series. In medieval music, the third was considered a dissonance and was used sparingly - and actually, when you're using Pythagorean tuning, it really is a dissonance - but most modern harmonies are built from thirds (see Triads ). In fact, the common harmonic tradition that includes everything from Baroque counterpoint to modern rock is often called triadic harmony .

Some modern Non-Western music traditions, which have a very different approach to melody and harmony, still base their tuning on the perfect fifth. Wolf fifths and ugly thirds are not a problem in these traditions, which build each mode within the framework of the perfect fifth, retuning for different modes as necessary. To read a little about one such tradition, please see Indian Classical Music: Tuning and Ragas .

The mean-tone system, in order to have pleasant-sounding thirds, takes rather the opposite approach from the Pythagorean. It uses the pure major third . In this system, the whole tone (or whole step ) is considered to be exactly half of the pure major third. This is the mean , or average, of the two tones, that gives the system its name. A semitone (or half step ) is exactly half (another mean) of a whole tone.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Special subjects in music theory' conversation and receive update notifications?