| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Phillis Wheatley ( [link] ) was born in Africa in 1753 and sold as a slave to the Wheatley family of Boston; her African name is lost to posterity. Although most slaves in the eighteenth century had no opportunities to learn to read and write, Wheatley achieved full literacy and went on to become one of the best-known poets of the time, although many doubted her authorship of her poems because of her race.

Wheatley’s poems reflected her deep Christian beliefs. In the poem below, how do her views on Christianity affect her views on slavery?

Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

“Their colour is a diabolic dye.”

Remember, Christians, Negroes, black as Cain,

May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.

—Phillis Wheatley, “On Being Brought from Africa to America”

Slavery offered the most glaring contradiction between the idea of equality stated in the Declaration of Independence (“all men are created equal”) and the reality of race relations in the late eighteenth century.

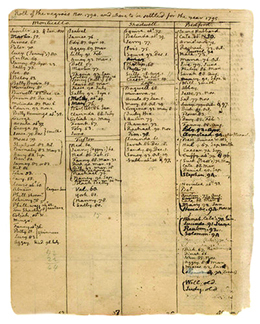

Racism shaped white views of blacks. Although he penned the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson owned more than one hundred slaves, of whom he freed only a few either during his lifetime or in his will ( [link] ). He thought blacks were inferior to whites, dismissing Phillis Wheatley by arguing, “Religion indeed has produced a Phillis Wheatley; but it could not produce a poet.” White slaveholders took their female slaves as mistresses, as most historians agree that Jefferson did with one of his slaves, Sally Hemings. Together, they had several children.

Browse the Thomas Jefferson Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society to examine Jefferson’s “farm books,” in which he kept records of his land holdings, animal husbandry, and slaves, including specific references to Sally Hemings.

Jefferson understood the contradiction fully, and his writings reveal hard-edged racist assumptions. In his Notes on the State of Virginia in the 1780s, Jefferson urged the end of slavery in Virginia and the removal of blacks from that state. He wrote: “It will probably be asked, Why not retain and incorporate the blacks into the state, and thus save the expense of supplying, by importation of white settlers, the vacancies they will leave? Deep rooted prejudices entertained by the whites; ten thousand recollections, by the blacks, of the injuries they have sustained; new provocations; the real distinctions which nature has made; and many other circumstances, will divide us into parties, and produce convulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of the one or the other race. —To these objections, which are political, may be added others, which are physical and moral.” Jefferson envisioned an “empire of liberty” for white farmers and relied on the argument of sending blacks out of the United States, even if doing so would completely destroy the slaveholders’ wealth in their human property.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?