| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

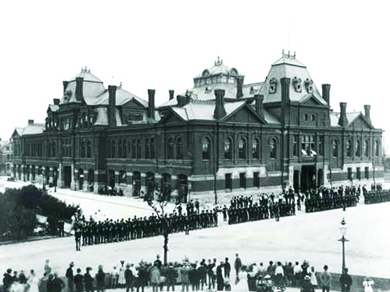

Two years later, in 1894, the Pullman Strike was another disaster for unionized labor. The crisis began in the company town of Pullman, Illinois, where Pullman “sleeper” cars were manufactured for America’s railroads. When the depression of 1893 unfolded in the wake of the failure of several northeastern railroad companies, mostly due to overconstruction and poor financing, company owner George Pullman fired three thousand of the factory’s six thousand employees, cut the remaining workers’ wages by an average of 25 percent, and then continued to charge the same high rents and prices in the company homes and store where workers were required to live and shop. Workers began the strike on May 11, when Eugene V. Debs, the president of the American Railway Union, ordered rail workers throughout the country to stop handling any trains that had Pullman cars on them. In practicality, almost all of the trains fell into this category, and, therefore, the strike created a nationwide train stoppage, right on the heels of the depression of 1893. Seeking justification for sending in federal troops, President Grover Cleveland turned to his attorney general, who came up with a solution: Attach a mail car to every train and then send in troops to ensure the delivery of the mail. The government also ordered the strike to end; when Debs refused, he was arrested and imprisoned for his interference with the delivery of U.S. mail. The image below ( [link] ) shows the standoff between federal troops and the workers. The troops protected the hiring of new workers, thus rendering the strike tactic largely ineffective. The strike ended abruptly on July 13, with no labor gains and much lost in the way of public opinion.

The following excerpt is a reflection from George Estes, an organizer and member of the Order of Railroad Telegraphers, a labor organization at the end of the nineteenth century. His perspective on the ways that labor and management related to each other illustrates the difficulties at the heart of their negotiations. He notes that, in this era, the two groups saw each other as enemies and that any gain by one was automatically a loss by the other.

I have always noticed that things usually have to get pretty bad before they get any better. When inequities pile up so high that the burden is more than the underdog can bear, he gets his dander up and things begin to happen. It was that way with the telegraphers’ problem. These exploited individuals were determined to get for themselves better working conditions—higher pay, shorter hours, less work which might not properly be classed as telegraphy, and the high and mighty Mr. Fillmore [railroad company president] was not going to stop them. It was a bitter fight. At the outset, Mr. Fillmore let it be known, by his actions and comments, that he held the telegraphers in the utmost contempt.

With the papers crammed each day with news of labor strife—and with two great labor factions at each other’s throats, I am reminded of a parallel in my own early and more active career. Shortly before the turn of the century, in 1898 and 1899 to be more specific, I occupied a position with regard to a certain class of skilled labor, comparable to that held by the Lewises and Greens of today. I refer, of course, to the telegraphers and station agents. These hard-working gentlemen—servants of the public—had no regular hours, performed a multiplicity of duties, and, considering the service they rendered, were sorely and inadequately paid. A telegrapher’s day included a considerable number of chores that present-day telegraphers probably never did or will do in the course of a day’s work. He used to clean and fill lanterns, block lights, etc. Used to do the janitor work around the small town depot, stoke the pot-bellied stove of the waiting-room, sweep the floors, picking up papers and waiting-room litter. . . .

Today, capital and labor seem to understand each other better than they did a generation or so ago. Capital is out to make money. So is labor—and each is willing to grant the other a certain amount of tolerant leeway, just so he doesn’t go too far. In the old days there was a breach as wide as the Pacific separating capital and labor. It wasn’t money altogether in those days, it was a matter of principle. Capital and labor couldn’t see eye to eye on a single point. Every gain that either made was at the expense of the other, and was fought tooth and nail. No difference seemed ever possible of amicable settlement. Strikes were riots. Murder and mayhem was common. Railroad labor troubles were frequent. The railroads, in the nineties, were the country’s largest employers. They were so big, so powerful, so perfectly organized themselves—I mean so in accord among themselves as to what treatment they felt like offering the man who worked for them—that it was extremely difficult for labor to gain a single advantage in the struggle for better conditions.

—George Estes, interview with Andrew Sherbert, 1938

After the Civil War, as more and more people crowded into urban areas and joined the ranks of wage earners, the landscape of American labor changed. For the first time, the majority of workers were employed by others in factories and offices in the cities. Factory workers, in particular, suffered from the inequity of their positions. Owners had no legal restrictions on exploiting employees with long hours in dehumanizing and poorly paid work. Women and children were hired for the lowest possible wages, but even men’s wages were barely enough upon which to live.

Poor working conditions, combined with few substantial options for relief, led workers to frustration and sporadic acts of protest and violence, acts that rarely, if ever, gained them any lasting, positive effects. Workers realized that change would require organization, and thus began early labor unions that sought to win rights for all workers through political advocacy and owner engagement. Groups like the National Labor Union and Knights of Labor both opened their membership to any and all wage earners, male or female, black or white, regardless of skill. Their approach was a departure from the craft unions of the very early nineteenth century, which were unique to their individual industries. While these organizations gained members for a time, they both ultimately failed when public reaction to violent labor strikes turned opinion against them. The American Federation of Labor, a loose affiliation of different unions, grew in the wake of these universal organizations, although negative publicity impeded their work as well. In all, the century ended with the vast majority of American laborers unrepresented by any collective or union, leaving them vulnerable to the power wielded by factory ownership.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?