| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Anxious to capitalize on the disarray within the Republican Party, as well as to return to the White House for the first time in nearly thirty years, the Democratic Party chose to court the Mugwump vote by nominating Grover Cleveland, the reform governor from New York who had built a reputation by attacking machine politics in New York City. Despite several personal charges against him for having fathered a child out of wedlock, Cleveland managed to hold on for a close victory with a margin of less than thirty thousand votes.

Cleveland’s record on civil service reform added little to the initial blows struck by President Arthur. After electing the first Democratic president since 1856, the Democrats could actually make great use of the spoils system. Cleveland was, however, a notable reform president in terms of business regulation and tariffs. When the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1886 that individual states could not regulate interstate transportation, Cleveland urged Congress to pass the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. Among several other powers, this law created the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to oversee railroad prices and ensure that they remained reasonable to all customers. This was an important shift. In the past, railroads had granted special rebates to big businesses, such as John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, while charging small farmers with little economic muscle exorbitant rates. Although the act eventually provided for real regulation of the railroad industry, initial progress was slow due to the lack of enforcement power held by the ICC. Despite its early efforts to regulate railroad rates, the U.S. Supreme Court undermined the commission in Interstate Commerce Commission v. Cincinnati, New Orleans, and Texas Pacific Railway Cos. in 1897. Rate regulations were limits on profits that, in the opinion of a majority of the justices, violated the Fourteenth Amendment protection against depriving persons of their property without due process of the law.

As for tariff reform, Cleveland agreed with Arthur’s position that tariffs remained far too high and were clearly designed to protect big domestic industries at the expense of average consumers who could benefit from international competition. While the general public applauded Cleveland’s efforts at both civil service and tariff reform, influential businessmen and industrialists remained adamant that the next president must restore the protective tariffs at all costs.

To counter the Democrats’ re-nomination of Cleveland, the Republican Party turned to Benjamin Harrison, grandson of former president William Henry Harrison. Although Cleveland narrowly won the overall popular vote, Harrison rode the influential coattails of several businessmen and party bosses to win the key electoral states of New York and New Jersey, where party officials stressed Harrison’s support for a higher tariff, and thus secure the White House. Not surprisingly, after Harrison’s victory, the United States witnessed a brief return to higher tariffs and a strengthening of the spoils system. In fact, the McKinley Tariff raised some rates as much as 50 percent, which was the highest tariff in American history to date.

Some of Harrison’s policies were intended to offer relief to average Americans struggling with high costs and low wages, but remained largely ineffective. First, the Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890 sought to prohibit business monopolies as “conspiracies in restraint of trade,” but it was seldom enforced during the first decade of its existence. Second, the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of the same year required the U.S. Treasury to mint over four million ounces of silver into coins each month to circulate more cash into the economy, raise prices for farm goods, and help farmers pay their way out of debt. But the measure could not undo the previous “hard money” policies that had deflated prices and pulled farmers into well-entrenched cycles of debt. Other measures proposed by Harrison intended to support African Americans, including a Force Bill to protect voters in the South, as well as an Education Bill designed to support public education and improve literacy rates among African Americans, also met with defeat.

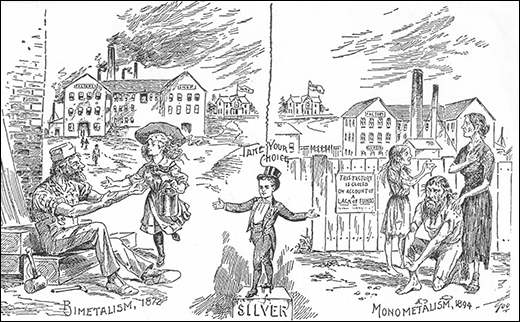

Although political corruption, the spoils system, and the question of tariff rates were popular discussions of the day, none were more relevant to working-class Americans and farmers than the issue of the nation’s monetary policy and the ongoing debate of gold versus silver ( [link] ). There had been frequent attempts to establish a bimetallic standard, which in turn would have created inflationary pressures and placed more money into circulation that could have subsequently benefitted farmers. But the government remained committed to the gold standard, including the official demonetizing of silver altogether in 1873. Such a stance greatly benefitted prominent businessmen engaged in foreign trade while forcing more farmers and working-class Americans into greater debt.

As farmers and working-class Americans sought the means by which to pay their bills and other living expenses, especially in the wake of increased tariffs as the century came to a close, many saw adherence to a strict gold standard as their most pressing problem. With limited gold reserves, the money supply remained constrained. At a minimum, a return to a bimetallic policy that would include the production of silver dollars would provide some relief. However, the aforementioned Sherman Silver Purchase Act was largely ineffective to combat the growing debts that many Americans faced. Under the law, the federal government purchased 4.5 million ounces of silver on a monthly basis in order to mint silver dollars. However, many investors exchanged the bank notes with which the government purchased the silver for gold, thus severely depleting the nation’s gold reserve. Fearing the latter, President Grover Cleveland signed the act’s repeal in 1893. This lack of meaningful monetary measures from the federal government would lead one group in particular who required such assistance—American farmers—to attempt to take control over the political process itself.

All told, from 1872 through 1892, Gilded Age politics were little more than political showmanship. The political issues of the day, including the spoils system versus civil service reform, high tariffs versus low, and business regulation, all influenced politicians more than the country at large. Very few measures offered direct assistance to Americans who continued to struggle with the transformation into an industrial society; the inefficiency of a patronage-driven federal government, combined with a growing laissez-faire attitude among the American public, made the passage of effective legislation difficult. Some of Harrison’s policies, such as the Sherman Anti-Trust Act and the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, aimed to provide relief but remained largely ineffective.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?