| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

In the 1870s, Irish coal miners in eastern Pennsylvania formed a secret organization known as the Molly Maguires , named for the famous Irish patriot. Through a series of scare tactics that included kidnappings, beatings, and even murder, the Molly Maguires sought to bring attention to the miners’ plight, as well as to cause enough damage and concern to the mine owners that the owners would pay attention to their concerns. Owners paid attention, but not in the way that the protesters had hoped. They hired detectives to pose as miners and mingle among the workers to obtain the names of the Molly Maguires. By 1875, they had acquired the names of twenty-four suspected Maguires, who were subsequently convicted of murder and violence against property. All were convicted and ten were hanged in 1876, at a public “Day of the Rope.” This harsh reprisal quickly crushed the remaining Molly Maguires movement. The only substantial gain the workers had from this episode was the knowledge that, lacking labor organization, sporadic violent protest would be met by escalated violence.

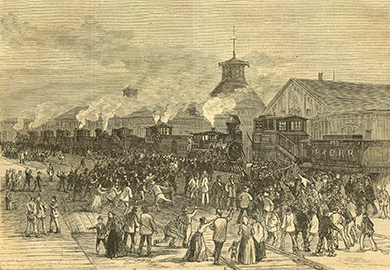

Public opinion was not sympathetic towards labor’s violent methods as displayed by the Molly Maguires. But the public was further shocked by some of the harsh practices employed by government agents to crush the labor movement, as seen the following year in the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. After incurring a significant pay cut earlier that year, railroad workers in West Virginia spontaneously went on strike and blocked the tracks ( [link] ). As word spread of the event, railroad workers across the country joined in sympathy, leaving their jobs and committing acts of vandalism to show their frustration with the ownership. Local citizens, who in many instances were relatives and friends, were largely sympathetic to the railroad workers’ demands.

The most significant violent outbreak of the railroad strike occurred in Pittsburgh, beginning on July 19. The governor ordered militiamen from Philadelphia to the Pittsburgh roundhouse to protect railroad property. The militia opened fire to disperse the angry crowd and killed twenty individuals while wounding another twenty-nine. A riot erupted, resulting in twenty-four hours of looting, violence, fire, and mayhem, and did not die down until the rioters wore out in the hot summer weather. In a subsequent skirmish with strikers while trying to escape the roundhouse, militiamen killed another twenty individuals. Violence erupted in Maryland and Illinois as well, and President Hayes eventually sent federal troops into major cities to restore order. This move, along with the impending return of cooler weather that brought with it the need for food and fuel, resulted in striking workers nationwide returning to the railroad. The strike had lasted for forty-five days, and they had gained nothing but a reputation for violence and aggression that left the public less sympathetic than ever. Dissatisfied laborers began to realize that there would be no substantial improvement in their quality of life until they found a way to better organize themselves.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?