| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

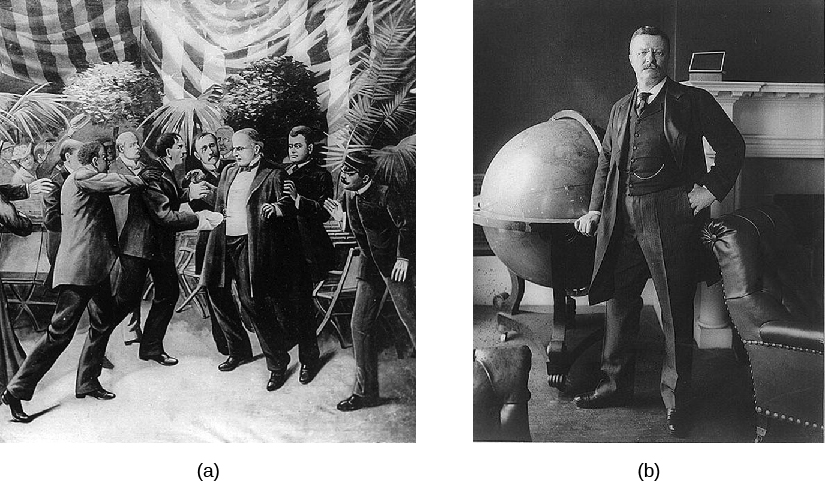

The most visible, though arguably the least powerful, member of a president’s cabinet is the vice president. Throughout most of the nineteenth and into the twentieth century, the vast majority of vice presidents took very little action in the office unless fate intervened. Few presidents consulted with their running mates. Indeed, until the twentieth century, many presidents had little to do with the naming of their running mate at the nominating convention. The office was seen as a form of political exile, and that motivated Republicans to name Theodore Roosevelt as William McKinley’s running mate in 1900. The strategy was to get the ambitious politician out of the way while still taking advantage of his popularity. This scheme backfired, however, when McKinley was assassinated and Roosevelt became president ( [link] ).

Vice presidents were often sent on minor missions or used as mouthpieces for the administration, often with a sharp edge. Richard

Nixon ’s vice president Spiro

Agnew is an example. But in the 1970s, starting with Jimmy Carter, presidents made a far more conscious effort to make their vice presidents part of the governing team, placing them in charge of increasingly important issues. Sometimes, as in the case of Bill

Clinton and Al

Gore , the partnership appeared to be smooth if not always harmonious. In the case of George W. Bush and his very experienced vice president Dick

Cheney , observers speculated whether the vice president might have exercised too much influence. Barack

Obama ’s choice for a running mate and subsequent two-term vice president, former Senator Joseph

Biden , was picked for his experience, especially in foreign policy. President Obama relied on Vice President Biden for advice throughout his tenure. In any case, the vice presidency is no longer quite as weak as it once was, and a capable vice president can do much to augment the president’s capacity to govern across issues if the president so desires.

Having secured election, the incoming president must soon decide how to deliver upon what was promised during the campaign. The chief executive must set priorities, chose what to emphasize, and formulate strategies to get the job done. He or she labors under the shadow of a measure of presidential effectiveness known as the first hundred days in office, a concept popularized during Franklin Roosevelt’s first term in the 1930s. While one hundred days is possibly too short a time for any president to boast of any real accomplishments, most presidents do recognize that they must address their major initiatives during their first two years in office. This is the time when the president is most powerful and is given the benefit of the doubt by the public and the media (aptly called the honeymoon period), especially if he or she enters the White House with a politically aligned Congress, as Barack Obama did. However, recent history suggests that even one-party control of Congress and the presidency does not ensure efficient policymaking. This difficulty is due as much to divisions within the governing party as to obstructionist tactics skillfully practiced by the minority party in Congress. Democratic president Jimmy Carter’s battles with a Congress controlled by Democratic majorities provide a good case in point.

The incoming president must deal to some extent with the outgoing president’s last budget proposal. While some modifications can be made, it is more difficult to pursue new initiatives immediately. Most presidents are well advised to prioritize what they want to achieve during the first year in office and not lose control of their agenda. At times, however, unanticipated events can determine policy, as happened in 2001 when nineteen hijackers perpetrated the worst terrorist attack in U.S. history and transformed U.S. foreign and domestic policy in dramatic ways.

Moreover, a president must be sensitive to what some scholars have termed “political time,” meaning the circumstances under which he or she assumes power. Sometimes, the nation is prepared for drastic proposals to solve deep and pressing problems that cry out for immediate solutions, as was the case following the 1932 election of FDR at the height of the Great Depression. Most times, however, the country is far less inclined to accept revolutionary change. Being an effective president means recognizing the difference.

The first act undertaken by the new president—the delivery of an inaugural address —can do much to set the tone for what is intended to follow. While such an address may be an exercise in rhetorical inspiration, it also allows the president to set forth priorities within the overarching vision of what he or she intends to do. Abraham Lincoln used his inaugural addresses to calm rising concerns in the South that he would act to overturn slavery. Unfortunately, this attempt at appeasement fell on deaf ears, and the country descended into civil war. Franklin Roosevelt used his first inaugural address to boldly proclaim that the country need not fear the change that would deliver it from the grip of the Great Depression, and he set to work immediately enlarging the federal government to that end. John F. Kennedy, who entered the White House at the height of the Cold War, made an appeal to talented young people around the country to help him make the world a better place. He followed up with new institutions like the Peace Corps, which sends young citizens around the world to work as secular missionaries for American values like democracy and free enterprise.

Listen to clips of the most famous inaugural address in presidential history at the Washington Post w ebsite.

It can be difficult for a new president to come to terms with both the powers of the office and the limitations of those powers. Successful presidents assume their role ready to make a smooth transition and to learn to work within the complex governmental system to fill vacant positions in the cabinet and courts, many of which require Senate confirmation. It also means efficiently laying out a political agenda and reacting appropriately to unexpected events. A new president has limited time to get things done and must take action with the political wind at his or her back.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'American government' conversation and receive update notifications?