| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

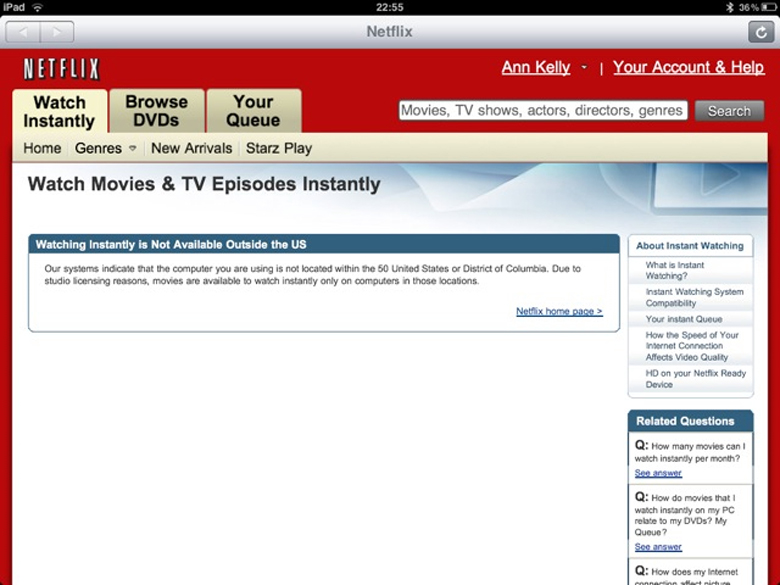

Imagine going to your favorite coffee shop and having the waiter inform you the pricing has changed. Instead of $3 for a cup of coffee, you will now be charged $2 for coffee, $1 for creamer, and $1 for your choice of sweetener. If you pay your usual $3 for a cup of coffee, you must choose between creamer and sweetener. If you want both, you now face an extra charge of $1. Sound absurd? Well, that is the situation Netflix customers found themselves in—a 60% price hike to retain the same service in 2011.

In early 2011, Netflix consumers paid about $10 a month for a package consisting of streaming video and DVD rentals. In July 2011, the company announced a packaging change. Customers wishing to retain both streaming video and DVD rental would be charged $15.98 per month, a price increase of about 60%. In 2014, Netflix also raised its streaming video subscription price from $7.99 to $8.99 per month for new U.S. customers. The company also changed its policy of 4K streaming content from $9.00 to $12.00 per month that year.

How would customers of the 18-year-old firm react? Would they abandon Netflix? Would the ease of access to other venues make a difference in how consumers responded to the Netflix price change? The answers to those questions will be explored in this chapter: the change in quantity with respect to a change in price, a concept economists call elasticity.

In this chapter, you will learn about:

Anyone who has studied economics knows the law of demand: a higher price will lead to a lower quantity demanded. What you may not know is how much lower the quantity demanded will be. Similarly, the law of supply shows that a higher price will lead to a higher quantity supplied. The question is: How much higher? This chapter will explain how to answer these questions and why they are critically important in the real world.

To find answers to these questions, we need to understand the concept of elasticity. Elasticity is an economics concept that measures responsiveness of one variable to changes in another variable. Suppose you drop two items from a second-floor balcony. The first item is a tennis ball. The second item is a brick. Which will bounce higher? Obviously, the tennis ball. We would say that the tennis ball has greater elasticity.

Consider an economic example. Cigarette taxes are an example of a “sin tax,” a tax on something that is bad for you, like alcohol. Cigarettes are taxed at the state and national levels. State taxes range from a low of 17 cents per pack in Missouri to $4.35 per pack in New York. The average state cigarette tax is $1.51 per pack. The 2014 federal tax rate on cigarettes was $1.01 per pack, but in 2015 the Obama Administration proposed raising the federal tax nearly a dollar to $1.95 per pack. The key question is: How much would cigarette purchases decline?

Taxes on cigarettes serve two purposes: to raise tax revenue for government and to discourage consumption of cigarettes. However, if a higher cigarette tax discourages consumption by quite a lot, meaning a greatly reduced quantity of cigarettes is sold, then the cigarette tax on each pack will not raise much revenue for the government. Alternatively, a higher cigarette tax that does not discourage consumption by much will actually raise more tax revenue for the government. Thus, when a government agency tries to calculate the effects of altering its cigarette tax, it must analyze how much the tax affects the quantity of cigarettes consumed. This issue reaches beyond governments and taxes; every firm faces a similar issue. Every time a firm considers raising the price that it charges, it must consider how much a price increase will reduce the quantity demanded of what it sells. Conversely, when a firm puts its products on sale, it must expect (or hope) that the lower price will lead to a significantly higher quantity demanded.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Principles of economics' conversation and receive update notifications?