| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

As before described, whether learning is adaptive or maladaptive depends on the relative costs, benefits, and level of parasitism within a system. In many cases, the cost of mistaken recognition and rejection is too high, especially when intraclutch variation is high, so the acceptor approach is favored. One special case, explained by the mafia hypothesis , is one in which parasitic birds raise the costs for rejection behavior to pressure hosts into acceptor schemes (see [link] ).

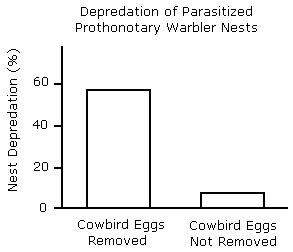

One study investigated the high levels at which the prothonotary Warbler ( Protonotaria citrea ) accepted cowbird eggs and concluded that rejection of eggs provoked retaliatory, mafia-like behavior from cowbirds. Nests which rejected eggs would later be depredated (Hoover et al 2006). In this case, the high cost of losing everything leads hosts to accept parasitic eggs, even if it reduces their own clutch sizes. In the case of cowbirds, where some of the host nestlings typically grow up in the nest with the parasites, it is to the host bird’s benefit to save some of the brood by accepting the parasitic chick than to lose all chicks (see [link] ).

As before described, rejection behavior is less common as parasitism levels decrease because the costs of mistaken rejection increase. Laws and Marthews 2003). created a model for which learning to recognize and reject parasitic nestlings would be beneficial for cowbird hosts (2003). When parasitism levels are high, the chance of properly rejecting parasitic eggs increases as well, so the rejecter strategy is favored. Additionally, low host nestling survival when raised with parasitic nestlings increases the benefit of adopting rejecter strategies because rejection of parasitic eggs would allow more of a host’s own nestlings to survive. In such cases, the benefits of choosing to reject would outweigh the costs of false rejection or accepting the parasitic eggs.

Even though rejection behavior produces a greater benefit when parasitism levels are high due to greater chance of correctly rejecting parasitic eggs, high levels of parasitism still inhibit selection for learning. Hauber et al. (2004) showed that repeated parasitism and increased costs of parasitism affect evolution of learning-based strategies simply because fewer offspring that possess the genes for learned behavior survive. One result they describe is that cowbird hosts that are smaller in size are more likely to adopt acceptor strategies. The small size results in greater costs from parasitism and fewer of their own nestlings survive. As a result, the appearance of learning-based rejection lags far behind for these smaller birds than it does for larger ones if the pressure is too high and prevents adaptive genes from surviving to the next generation.

Learning is beneficial for hosts of avian brood parasites only under certain conditions such as low parasitism rate and low intraclutch variation. Under other conditions, there may be other alternatives that are better. With the spread of many brood parasites, many previously naïve species have been exposed to the threats of parasitism and have been observed to display non-learned defenses (See [link] .)

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Mockingbird tales: readings in animal behavior' conversation and receive update notifications?