| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

By far, the most successful use of antivirals has been in the treatment of the retrovirus HIV, which causes a disease that, if untreated, is usually fatal within 10–12 years after infection. Anti-HIV drugs have been able to control viral replication to the point that individuals receiving these drugs survive for a significantly longer time than the untreated.

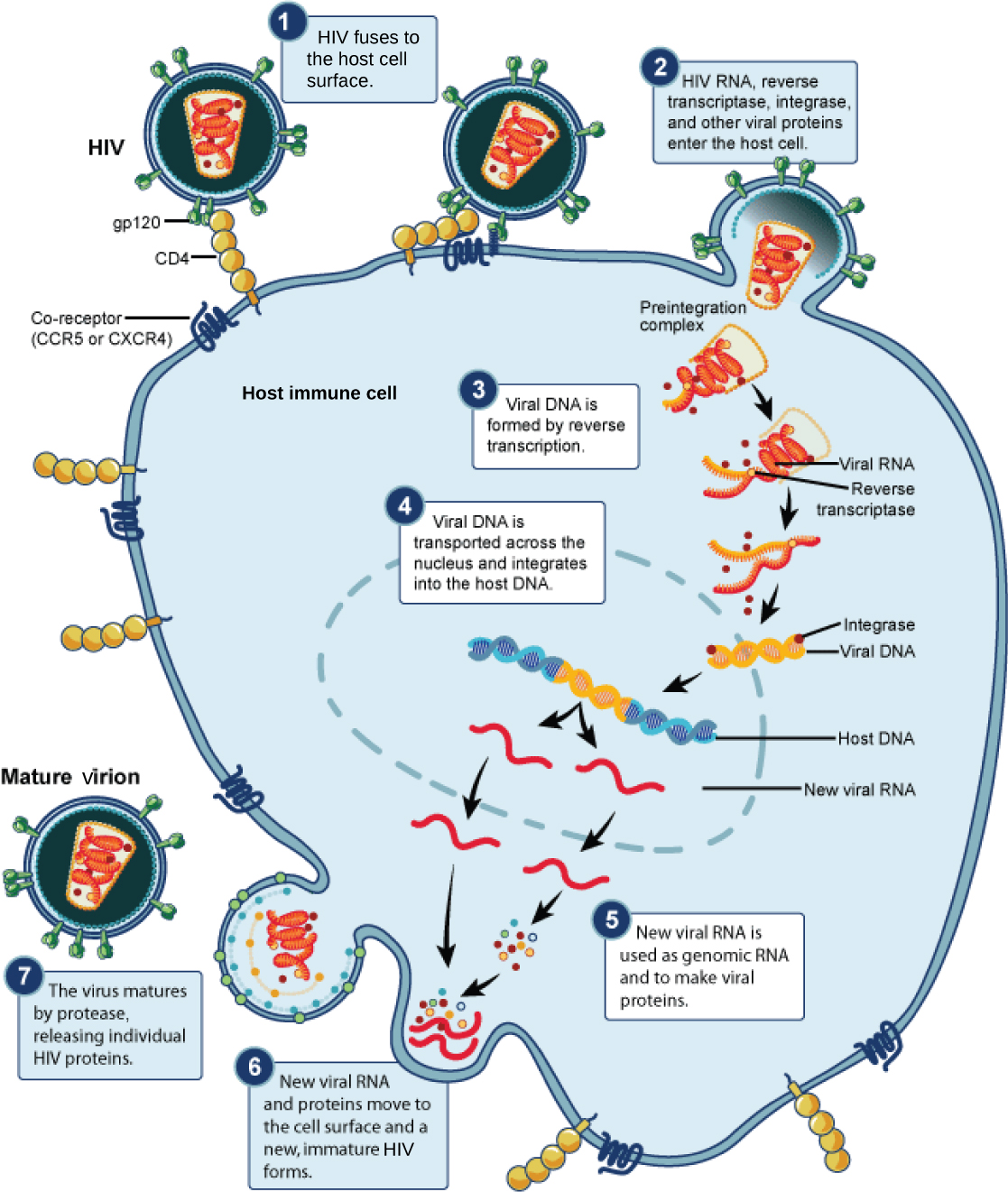

Anti-HIV drugs inhibit viral replication at many different phases of the HIV replicative cycle ( [link] ). Drugs have been developed that inhibit the fusion of the HIV viral envelope with the plasma membrane of the host cell (fusion inhibitors), the conversion of its RNA genome into double-stranded DNA (reverse transcriptase inhibitors), the integration of the viral DNA into the host genome (integrase inhibitors), and the processing of viral proteins (protease inhibitors).

When any of these drugs are used individually, the high mutation rate of the virus allows it to easily and rapidly develop resistance to the drug, limiting the drug’s effectiveness. The breakthrough in the treatment of HIV was the development of HAART, highly active anti-retroviral therapy, which involves a mixture of different drugs, sometimes called a drug “cocktail.” By attacking the virus at different stages of its replicative cycle, it is much more difficult for the virus to develop resistance to multiple drugs at the same time. Still, even with the use of combination HAART therapy, there is concern that, over time, the virus will develop resistance to this therapy. Thus, new anti-HIV drugs are constantly being developed with the hope of continuing the battle against this highly fatal virus.

Another medical use for viruses relies on their specificity and ability to kill the cells they infect. Oncolytic viruses are engineered in the laboratory specifically to attack and kill cancer cells. A genetically modified adenovirus known as H101 has been used since 2005 in clinical trials in China to treat head and neck cancers. The results have been promising, with a greater short-term response rate to the combination of chemotherapy and viral therapy than to chemotherapy treatment alone. This ongoing research may herald the beginning of a new age of cancer therapy, where viruses are engineered to find and specifically kill cancer cells, regardless of where in the body they may have spread.

A third use of viruses in medicine relies on their specificity and involves using bacteriophages in the treatment of bacterial infections. Bacterial diseases have been treated with antibiotics since the 1940s. However, over time, many bacteria have developed resistance to antibiotics. A good example is methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA, pronounced “mersa”), an infection commonly acquired in hospitals. This bacterium is resistant to a variety of antibiotics, making it difficult to treat. The use of bacteriophages specific for such bacteria would bypass their resistance to antibiotics and specifically kill them. Although phage therapy is in use in the Republic of Georgia to treat antibiotic-resistant bacteria, its use to treat human diseases has not been approved in most countries. However, the safety of the treatment was confirmed in the United States when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved spraying meats with bacteriophages to destroy the food pathogen Listeria. As more and more antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria evolve, the use of bacteriophages might be a potential solution to the problem, and the development of phage therapy is of much interest to researchers worldwide.

Viruses cause a variety of diseases in humans. Many of these diseases can be prevented by the use of viral vaccines, which stimulate protective immunity against the virus without causing major disease. Viral vaccines may also be used in active viral infections, boosting the ability of the immune system to control or destroy the virus. A series of antiviral drugs that target enzymes and other protein products of viral genes have been developed and used with mixed success. Combinations of anti-HIV drugs have been used to effectively control the virus, extending the lifespans of infected individuals. Viruses have many uses in medicines, such as in the treatment of genetic disorders, cancer, and bacterial infections.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Biology' conversation and receive update notifications?