| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Recall that at the point of fertilization, the oocyte has not yet completed meiosis; all secondary oocytes remain arrested in metaphase of meiosis II until fertilization. Only upon fertilization does the oocyte complete meiosis. The unneeded complement of genetic material that results is stored in a second polar body that is eventually ejected. At this moment, the oocyte has become an ovum, the female haploid gamete. The two haploid nuclei derived from the sperm and oocyte and contained within the egg are referred to as pronuclei. They decondense, expand, and replicate their DNA in preparation for mitosis. The pronuclei then migrate toward each other, their nuclear envelopes disintegrate, and the male- and female-derived genetic material intermingles. This step completes the process of fertilization and results in a single-celled diploid zygote with all the genetic instructions it needs to develop into a human.

Most of the time, a woman releases a single egg during an ovulation cycle. However, in approximately 1 percent of ovulation cycles, two eggs are released and both are fertilized. Two zygotes form, implant, and develop, resulting in the birth of dizygotic (or fraternal) twins. Because dizygotic twins develop from two eggs fertilized by two sperm, they are no more identical than siblings born at different times.

Much less commonly, a zygote can divide into two separate offspring during early development. This results in the birth of monozygotic (or identical) twins. Although the zygote can split as early as the two-cell stage, splitting occurs most commonly during the early blastocyst stage, with roughly 70–100 cells present. These two scenarios are distinct from each other, in that the twin embryos that separated at the two-cell stage will have individual placentas, whereas twin embryos that form from separation at the blastocyst stage will share a placenta and a chorionic cavity.

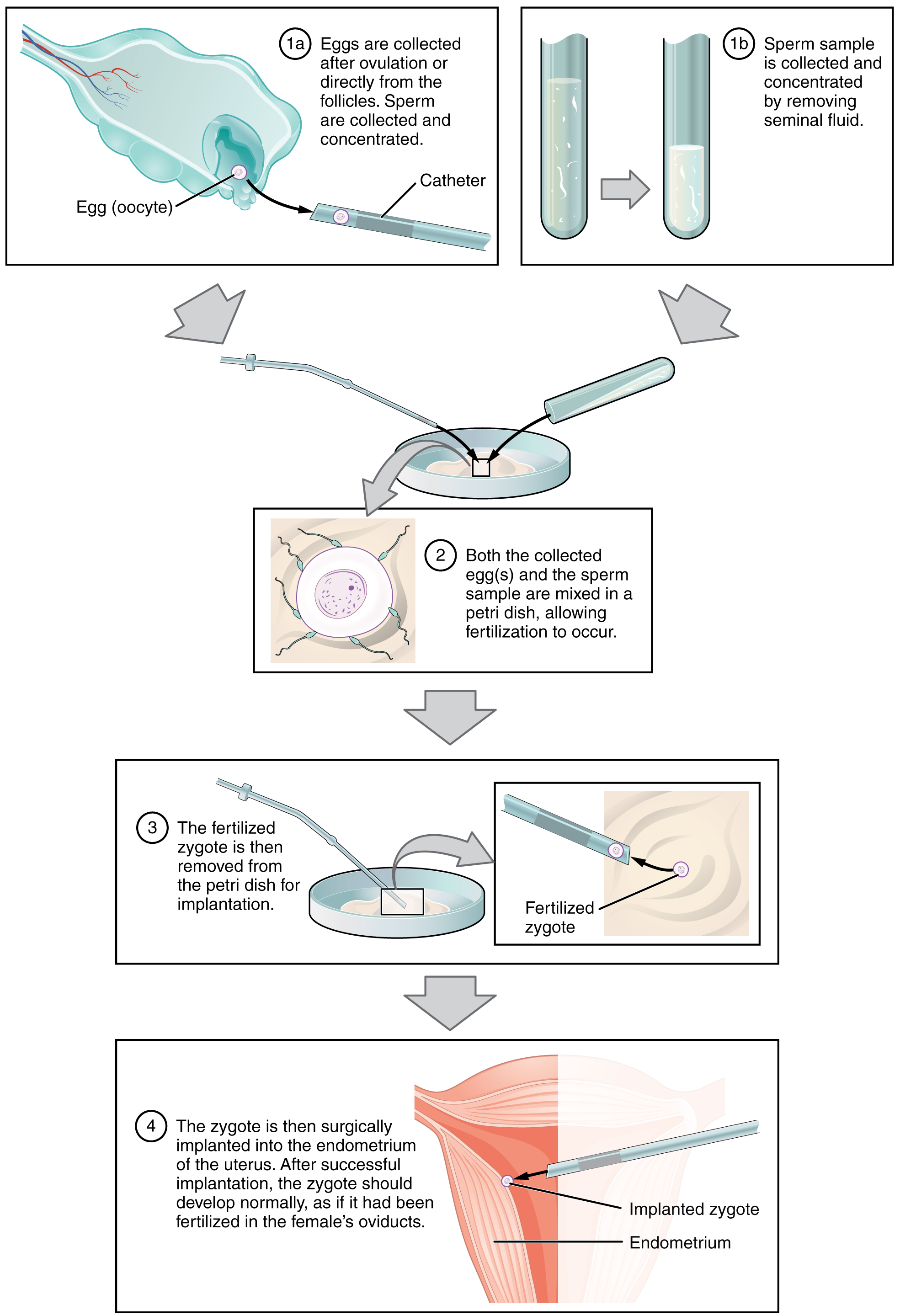

A typical IVF procedure begins with egg collection. A normal ovulation cycle produces only one oocyte, but the number can be boosted significantly (to 10–20 oocytes) by administering a short course of gonadotropins. The course begins with follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) analogs, which support the development of multiple follicles, and ends with a luteinizing hormone (LH) analog that triggers ovulation. Right before the ova would be released from the ovary, they are harvested using ultrasound-guided oocyte retrieval. In this procedure, ultrasound allows a physician to visualize mature follicles. The ova are aspirated (sucked out) using a syringe.

In parallel, sperm are obtained from the male partner or from a sperm bank. The sperm are prepared by washing to remove seminal fluid because seminal fluid contains a peptide, FPP (or, fertilization promoting peptide), that—in high concentrations—prevents capacitation of the sperm. The sperm sample is also concentrated, to increase the sperm count per milliliter.

Next, the eggs and sperm are mixed in a petri dish. The ideal ratio is 75,000 sperm to one egg. If there are severe problems with the sperm—for example, the count is exceedingly low, or the sperm are completely nonmotile, or incapable of binding to or penetrating the zona pellucida—a sperm can be injected into an egg. This is called intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI).

The embryos are then incubated until they either reach the eight-cell stage or the blastocyst stage. In the United States, fertilized eggs are typically cultured to the blastocyst stage because this results in a higher pregnancy rate. Finally, the embryos are transferred to a woman’s uterus using a plastic catheter (tube). [link] illustrates the steps involved in IVF.

IVF is a relatively new and still evolving technology, and until recently it was necessary to transfer multiple embryos to achieve a good chance of a pregnancy. Today, however, transferred embryos are much more likely to implant successfully, so countries that regulate the IVF industry cap the number of embryos that can be transferred per cycle at two. This reduces the risk of multiple-birth pregnancies.

The rate of success for IVF is correlated with a woman’s age. More than 40 percent of women under 35 succeed in giving birth following IVF, but the rate drops to a little over 10 percent in women over 40.

Go to this site to view resources covering various aspects of fertilization, including movies and animations showing sperm structure and motility, ovulation, and fertilization.

Hundreds of millions of sperm deposited in the vagina travel toward the oocyte, but only a few hundred actually reach it. The number of sperm that reach the oocyte is greatly reduced because of conditions within the female reproductive tract. Many sperm are overcome by the acidity of the vagina, others are blocked by mucus in the cervix, whereas others are attacked by phagocytic leukocytes in the uterus. Those sperm that do survive undergo a change in response to those conditions. They go through the process of capacitation, which improves their motility and alters the membrane surrounding the acrosome, the cap-like structure in the head of a sperm that contains the digestive enzymes needed for it to attach to and penetrate the oocyte.

The oocyte that is released by ovulation is protected by a thick outer layer of granulosa cells known as the corona radiata and by the zona pellucida, a thick glycoprotein membrane that lies just outside the oocyte’s plasma membrane. When capacitated sperm make contact with the oocyte, they release the digestive enzymes in the acrosome (the acrosomal reaction) and are thus able to attach to the oocyte and burrow through to the oocyte’s zona pellucida. One of the sperm will then break through to the oocyte’s plasma membrane and release its haploid nucleus into the oocyte. The oocyte’s membrane structure changes in response (cortical reaction), preventing any further penetration by another sperm and forming a fertilization membrane. Fertilization is complete upon unification of the haploid nuclei of the two gametes, producing a diploid zygote.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Anatomy & Physiology' conversation and receive update notifications?