| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Blood flow refers to the movement of blood through a vessel, tissue, or organ, and is usually expressed in terms of volume of blood per unit of time. It is initiated by the contraction of the ventricles of the heart. Ventricular contraction ejects blood into the major arteries, resulting in flow from regions of higher pressure to regions of lower pressure, as blood encounters smaller arteries and arterioles, then capillaries, then the venules and veins of the venous system. This section discusses a number of critical variables that contribute to blood flow throughout the body. It also discusses the factors that impede or slow blood flow, a phenomenon known as resistance .

As noted earlier, hydrostatic pressure is the force exerted by a fluid due to gravitational pull, usually against the wall of the container in which it is located. One form of hydrostatic pressure is blood pressure , the force exerted by blood upon the walls of the blood vessels or the chambers of the heart. Blood pressure may be measured in capillaries and veins, as well as the vessels of the pulmonary circulation; however, the term blood pressure without any specific descriptors typically refers to systemic arterial blood pressure—that is, the pressure of blood flowing in the arteries of the systemic circulation. In clinical practice, this pressure is measured in mm Hg and is usually obtained using the brachial artery of the arm.

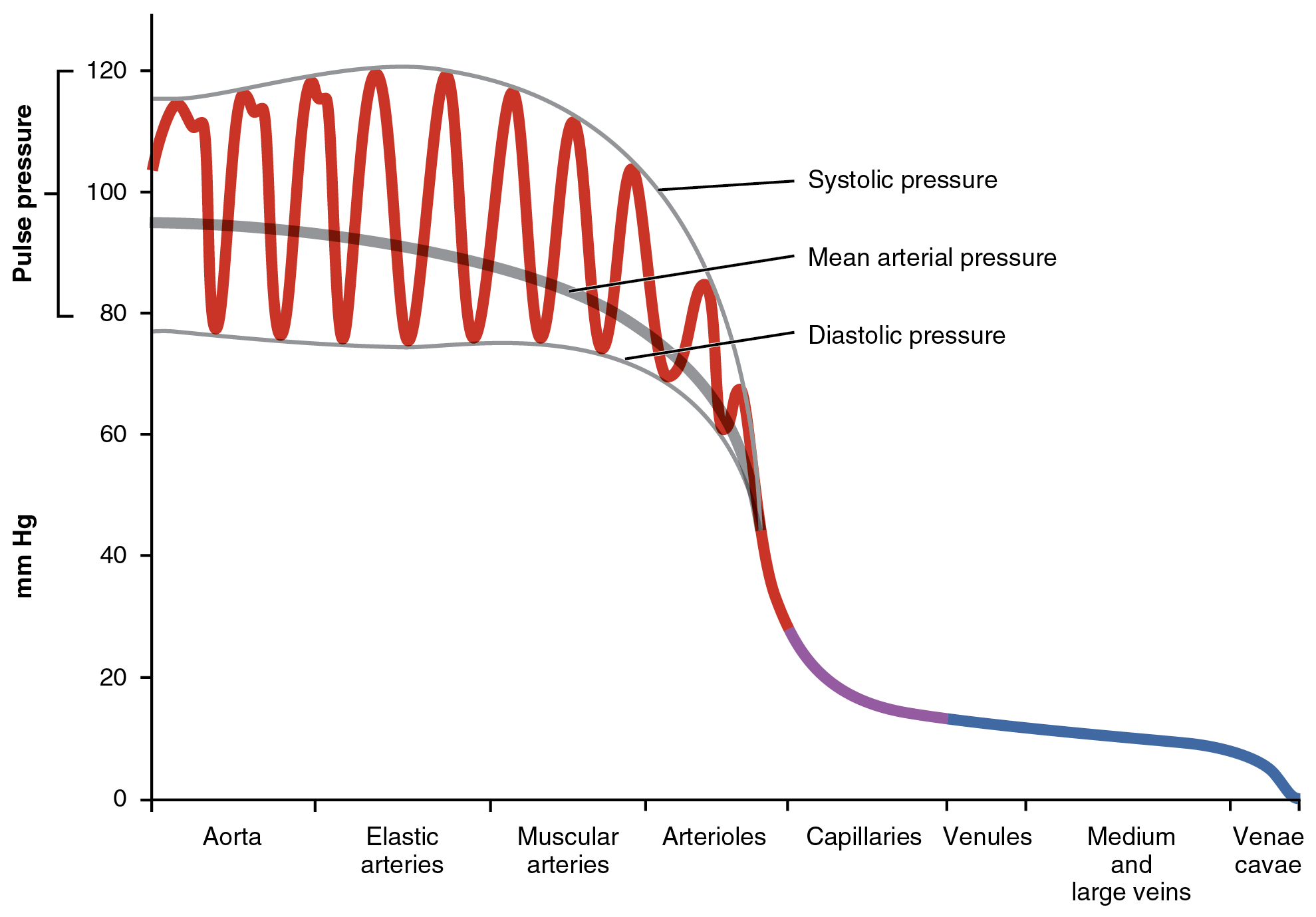

Arterial blood pressure in the larger vessels consists of several distinct components ( [link] ): systolic and diastolic pressures, pulse pressure, and mean arterial pressure.

When systemic arterial blood pressure is measured, it is recorded as a ratio of two numbers (e.g., 120/80 is a normal adult blood pressure), expressed as systolic pressure over diastolic pressure. The systolic pressure is the higher value (typically around 120 mm Hg) and reflects the arterial pressure resulting from the ejection of blood during ventricular contraction, or systole. The diastolic pressure is the lower value (usually about 80 mm Hg) and represents the arterial pressure of blood during ventricular relaxation, or diastole.

As shown in [link] , the difference between the systolic pressure and the diastolic pressure is the pulse pressure . For example, an individual with a systolic pressure of 120 mm Hg and a diastolic pressure of 80 mm Hg would have a pulse pressure of 40 mmHg.

Generally, a pulse pressure should be at least 25 percent of the systolic pressure. A pulse pressure below this level is described as low or narrow. This may occur, for example, in patients with a low stroke volume, which may be seen in congestive heart failure, stenosis of the aortic valve, or significant blood loss following trauma. In contrast, a high or wide pulse pressure is common in healthy people following strenuous exercise, when their resting pulse pressure of 30–40 mm Hg may increase temporarily to 100 mm Hg as stroke volume increases. A persistently high pulse pressure at or above 100 mm Hg may indicate excessive resistance in the arteries and can be caused by a variety of disorders. Chronic high resting pulse pressures can degrade the heart, brain, and kidneys, and warrant medical treatment.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Anatomy & Physiology' conversation and receive update notifications?